Take a journey through history and cultures, exploring ancient civilisations and contemporary nations.

In 138 BCE, General Zhang Qian of China’s Han Dynasty was sent on a diplomatic mission to develop economic and cultural links with the peoples of Central Asia. In so doing, he set in motion the creation of a transcontinental trade route that would shape the world as we know it today.

The Silk Road, as it would later be called, is neither an actual road nor a single route. It refers to the historic network of trade routes that stretched thousands of miles across Eurasia connecting China with Europe.

It was not only goods that travelled these routes but knowledge, religions and people too. Gunpowder, the magnetic compass, the printing press, and advanced mathematics all came to Europe from China and the Islamic world. Buddhism, Christianity and Islam each found new converts in the lands that opened up to the East and West.

These exchanges had a profound impact on the empires and civilisations through which they passed, giving them political, religious and cultural shape. By the late 16th century, the Silk Road had lost its prominence to new maritime trade routes but the legacy of interconnectivity and exchange endured.

Today, it is being reimagined on an unprecedented scale. Through China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Eurasia is the focus of the largest and most expensive infrastructure project in history. If realised, a massive network of roads, railways, pipelines and ports could connect as much as 65% of the world’s population and radically alter the flow of global trade. It is already beginning to reshape Eurasia, focusing world attention once again on the exchange of goods and ideas running from East to West.

We’re delighted to announce the forthcoming publication of The Silk Road: A Living History which will be published in September 2024.

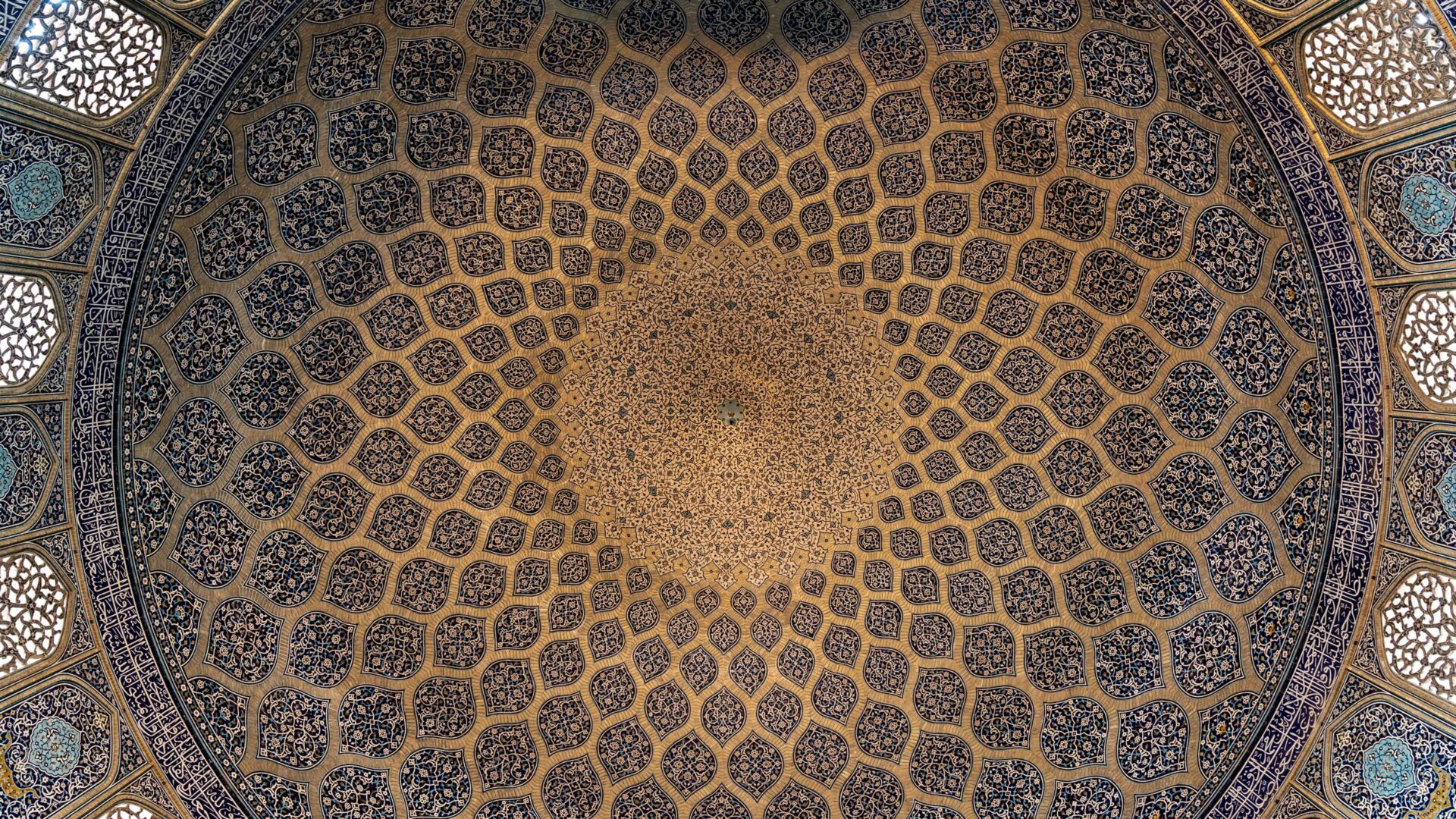

The book will present 160 photographs taken primarily on an overland journey photographer Christopher Wilton-Steer took from London to Beijing in 2019.

The Silk Road: A Living History exhibition invites you to take a journey from London to Beijing, encountering some of the people, places and cultures in-between.

Following successful outdoor exhibitions of The Silk Road: A Living History in London and Toronto, you can now take a journey along the world’s most celebrated trade routes from the comfort of your own home.

This digital format allows for the original photos to be displayed alongside video and audio content as well as photo essays and travel writing allowing you to explore even more of the Silk Road.

Enjoy the journey!

The Silk Road: A Living History exhibition was shown in public spaces in London and Toronto in 2021 and 2022.

If you are interested in hosting the exhibition, please get in touch.

Go beyond the exhibition and discover more about some of the people, places and cultures along the Silk Road through a selection of photo essays and travel writing.

Explore the cultural, economic and social heritage of the countries, cities and regions that lie along the Silk Road through this series of talks.

Visit the Aga Khan Foundation’s annual bazaar in King’s Cross and discover artisanal products from countries along the Silk Road including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and elsewhere. The 2023 Bazaar took place between 23-25 June.

Details about the next Silk Road Bazaar will be published in early 2024.

The Aga Khan Foundation and agencies of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) have been active in countries along the Silk Road for decades. AKDN is a long-term partner in the development of Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan. Alongside its partners, AKDN has channelled significant financial and human resources into economic, social and cultural development in these regions. Promoting pluralism, self-reliance and women’s empowerment have been central to those efforts.

AKDN’s initiatives are wide-ranging and include agriculture and food security, climate resilience, education, energy, enterprise development, financial services, healthcare, infrastructure, telecommunications and promoting civil society. It has also restored hundreds of historical monuments, parks and gardens and supported some of Central Asia’s greatest musicians to transmit their knowledge and perform on the world’s stage. AKDN’s overarching aim is to improve the quality of life.