Some aerial shots of Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast and its magnificent landscapes. GBAO comprises the easter half of Tajikistan and is home to the Pamir Mountains, also known as ‘the roof of the world’.

Murghab Мурғоб

At 3,650 metres above sea level, Murghab is the highest town in Tajikistan. Situated in the far east of the country near the border with China, it was founded by the Russians (as Pamirsky Post) in 1893 as their most advanced military outpost into Central Asia. Due to the altitude, only a few thousand people live here.

Murghab Мурғоб

Two Kyrgyz men greet each other in the streets of Murghab. Their nationality can be guessed at due to the distinctive traditionally Kyrgyz Kalpak hats they wear.

Local life on a journey through Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains

In the heart of Central Asia lie the dramatic Pamir Mountains; while the topography of this lofty region poses unique challenges to daily life, new initiatives have helped to bring fresh opportunities to some of Tajikistan’s remotest communities.

See Christopher Wilton-Steer’s photo essay in National Geographic.

Murghab Мурғоб

In the summer months, semi-nomadic Kyrgyz bring their yak to graze in the nearby pastures (yurts can be seen in the foreground) and retreat to the town during the bitterly cold winter months.

Tajikistan from above

Some aerial shots of Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast and its magnificent landscapes. GBAO comprises the easter half of Tajikistan and is home to the Pamir Mountains, also known as ‘the roof of the world’.

Murghab Мурғоб

The Aga Khan Foundation works with local artisans to help develop the local economy and sell their handicrafts to tourists who pass through Murghab along the Pamir Highway – the historic road and trade link that traverses Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Local life on a journey through Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains

In the heart of Central Asia lie the dramatic Pamir Mountains; while the topography of this lofty region poses unique challenges to daily life, new initiatives have helped to bring fresh opportunities to some of Tajikistan’s remotest communities.

See Christopher Wilton-Steer’s photo essay in National Geographic.

Vanj Valley Ванҷ води

One of the many beautiful valleys in the Pamir mountains of eastern Tajikistan. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and an ensuing civil war, mountain communities suffered hugely from a lack of food, healthcare, electricity and other key services. At its worst point, only 13% of the 200,000 population had access to electricity in this mountainous region.

Tajikistan from above

Some aerial shots of Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast and its magnificent landscapes. GBAO comprises the easter half of Tajikistan and is home to the Pamir Mountains, also known as ‘the roof of the world’.

Vanj Valley Ванҷ води

Since 2002, the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development has worked with several governments, including Germany, Norway, Switzerland, the UK and the US, as well as the EU and the World Bank to restore access to electricity. Today, through Pamir Energy, 96% of households now have access to clean, reliable and affordable energy.

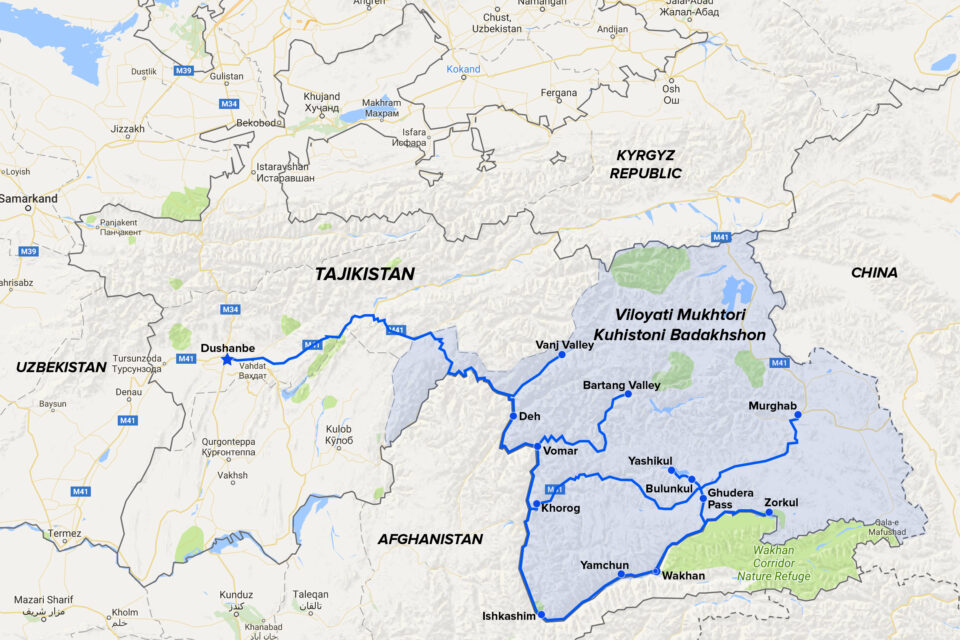

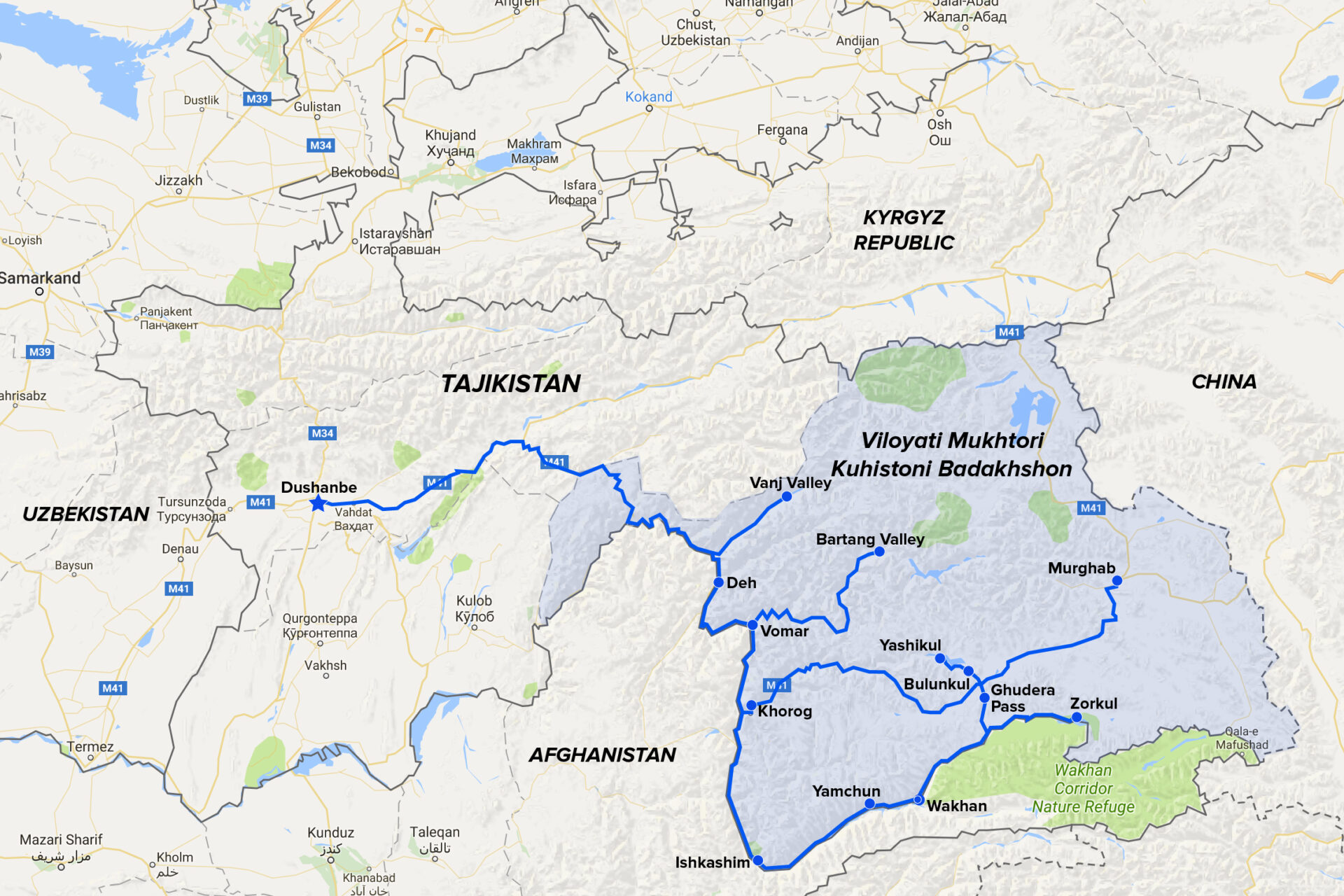

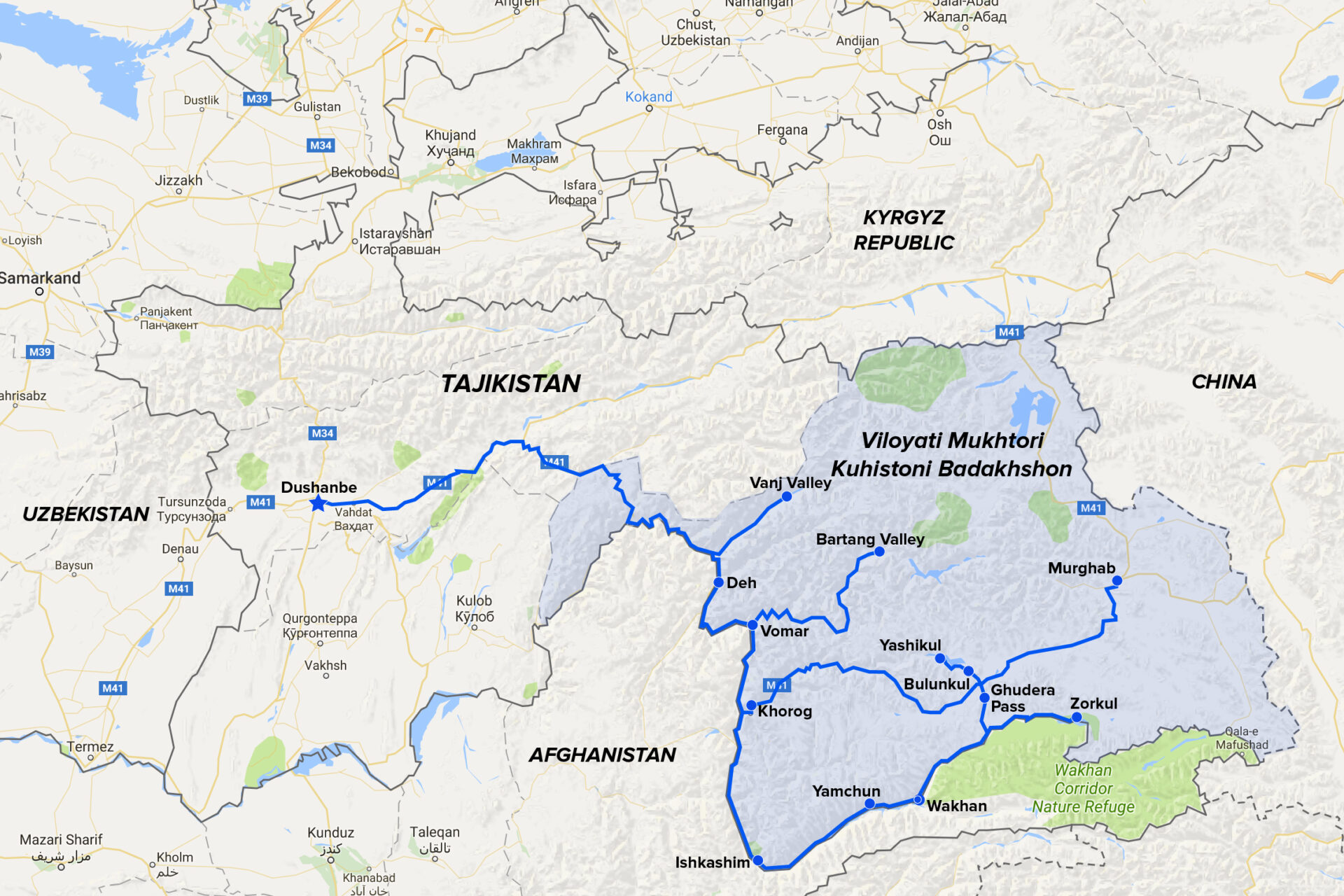

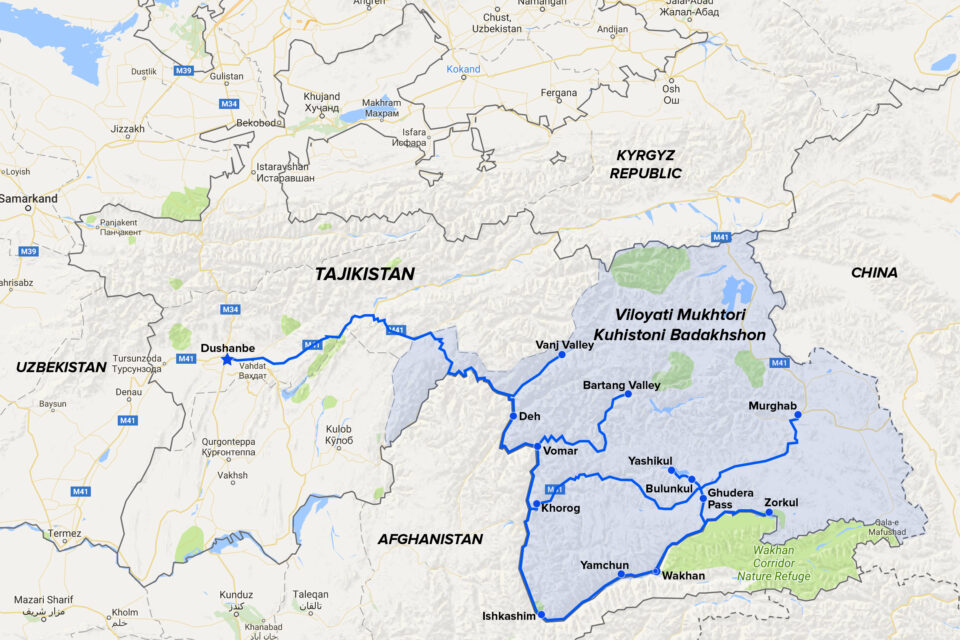

3,000KM ACROSS THE ROOF OF THE WORLD | On assignment in Eastern Tajikistan

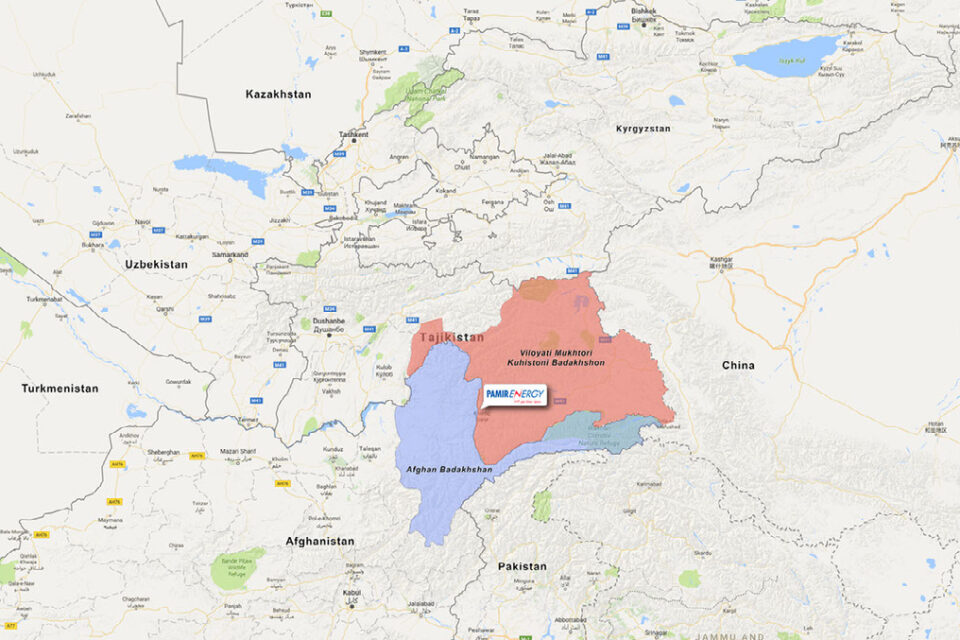

PAMIR ENERGY, KHOROG

I’m beckoned into Daler Jumaev’s office and offered a seat.

Daler is on a call with one of his engineers and is giving him some heat down the phone, his fists thumping his desk with each word. He’s speaking in Tajik but I think I understand the message: “I’m not interested in excuses. Get. It. Done.” I remember Daler once telling me, to get things done in Tajikistan, you need to be tough.

He hangs up, the momentary frustration has passed and he comes to greet me in that typical Daler way, with a huge grin and a bear hug. “Welcome Chris-tow-feerr! How was your flight?”

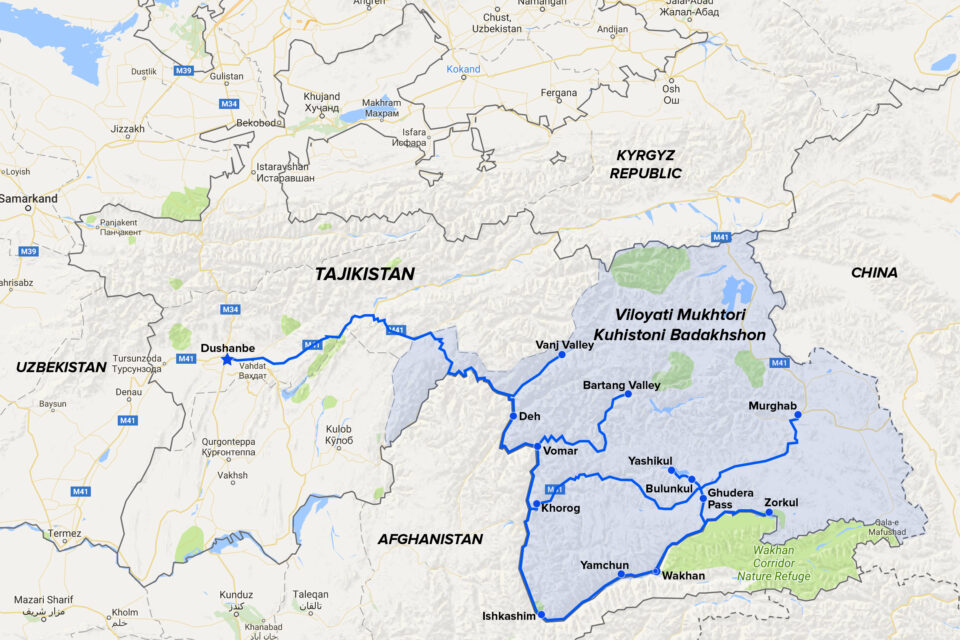

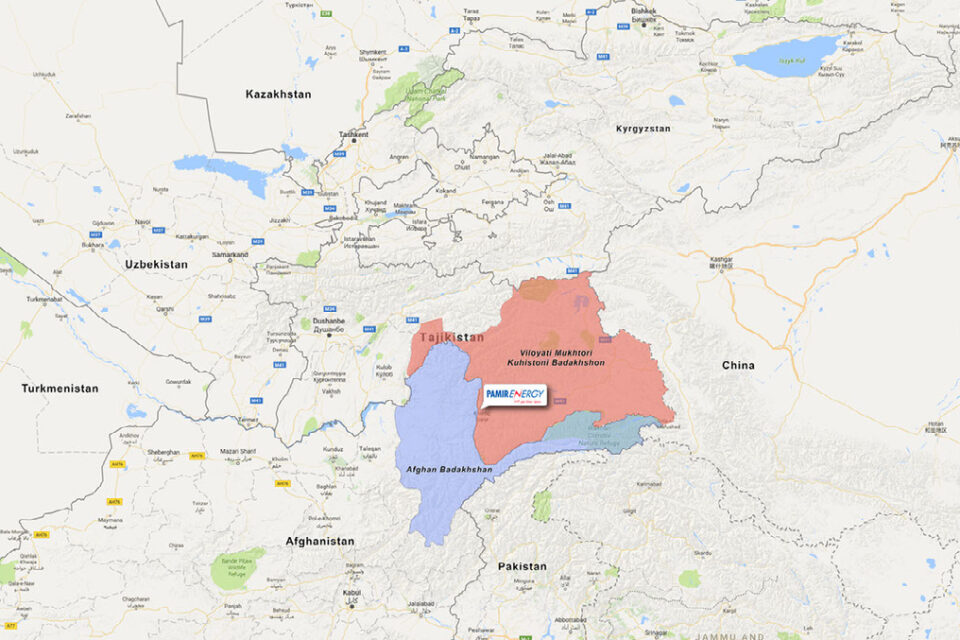

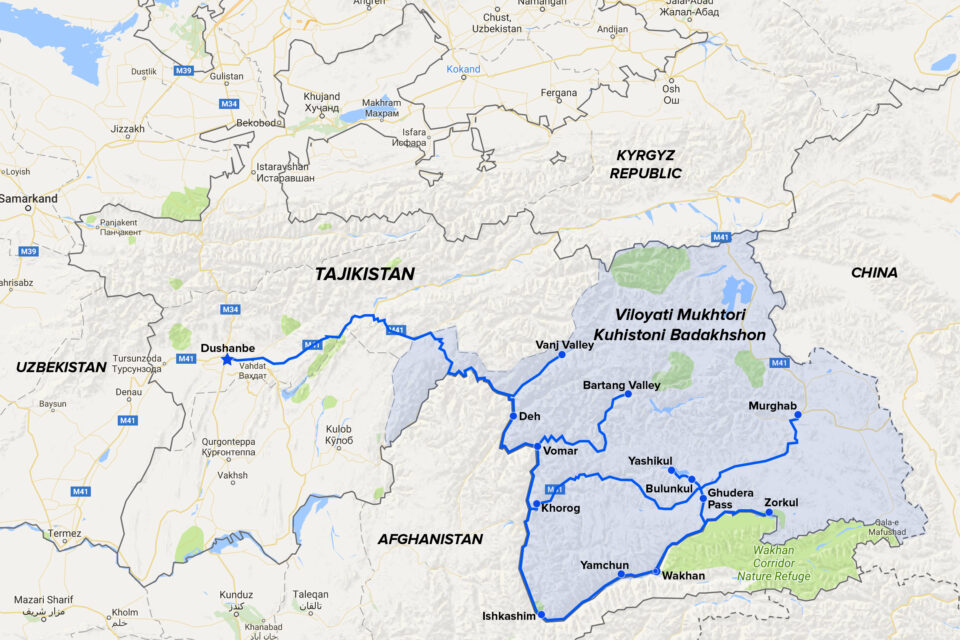

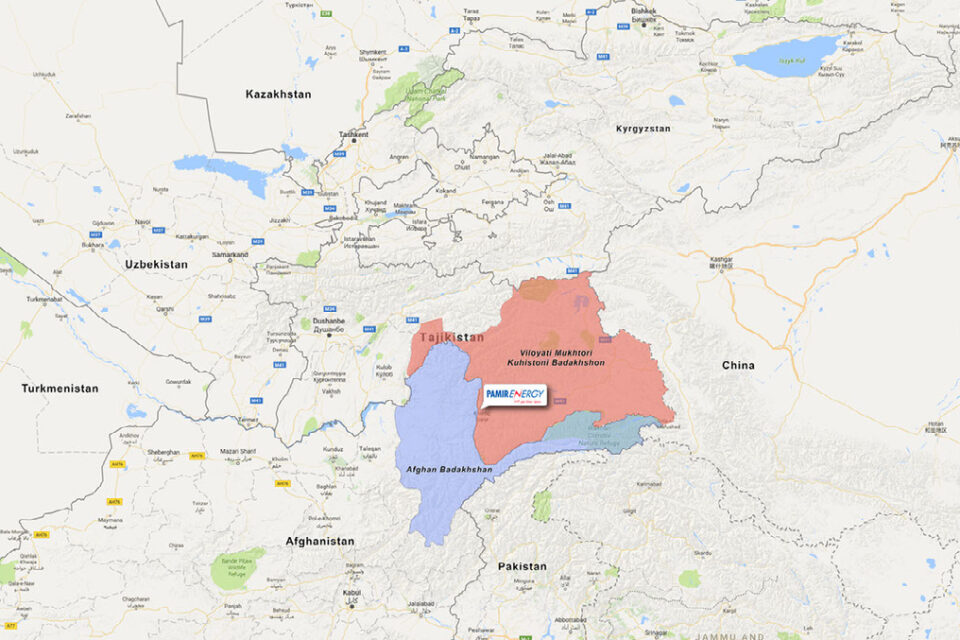

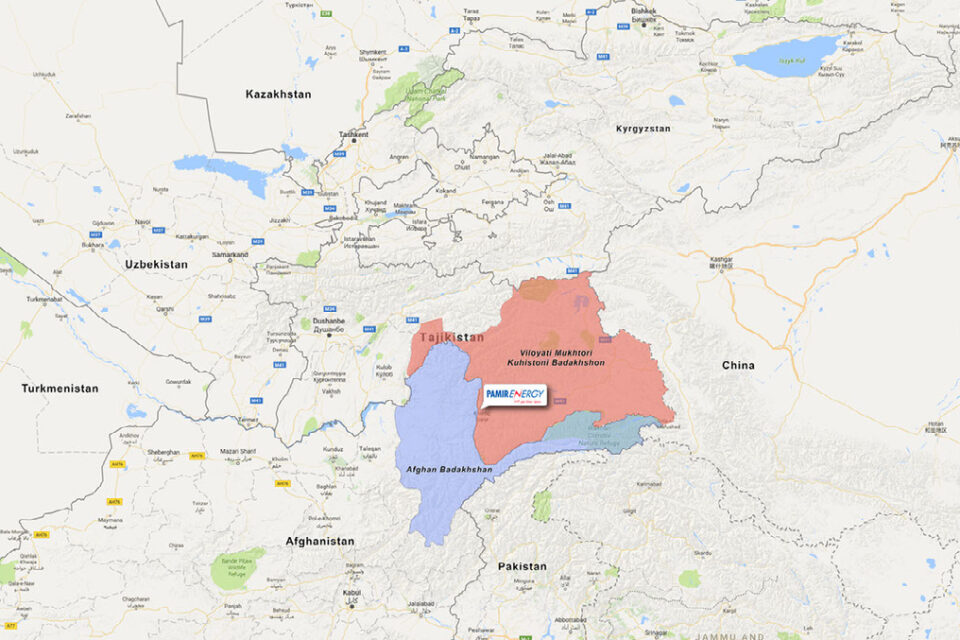

Daler Jumaev is the General Director of Pamir Energy; an off-grid energy company that owns and operates several small scale hydropower plants and a network of distribution lines spanning 4,300km across Viloyati Mukhtori Kuhistoni Badakhshon (VMKB); the eastern half of Tajikistan to you and me. Of the many hats Daler wears this is perhaps the most important one; over 250,000 people are relying on him to provide their electricity in this remote mountainous part of the world.

Daler has invited me to VMKB to photograph the Pamir Energy network and the people whose lives it touches. The company has a great story to tell.

Pamir Energy was established in 2002 to respond to the region’s dire energy needs that followed the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the ensuing civil war. At that time, only 13% of the population had access to electricity. Wood being the only readily available fuel, 70% of the region was deforested. Living standards and the quality of life declined dramatically throughout the 1990s.

This was the context in which the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), the Government of Tajikistan and the World Bank established Pamir Energy; Central Asia’s first public private partnership. It’s mission: to turn around a post-Soviet utility to provide clean and affordable energy 24 hours a day to the poor communities in the region.

Today, 96% of the population of VMKB are able to access energy; a remarkable achievement. In 2008 the company began to export electricity across the border to northern Afghanistan. Some villages are receiving electricity for the first time in their history.

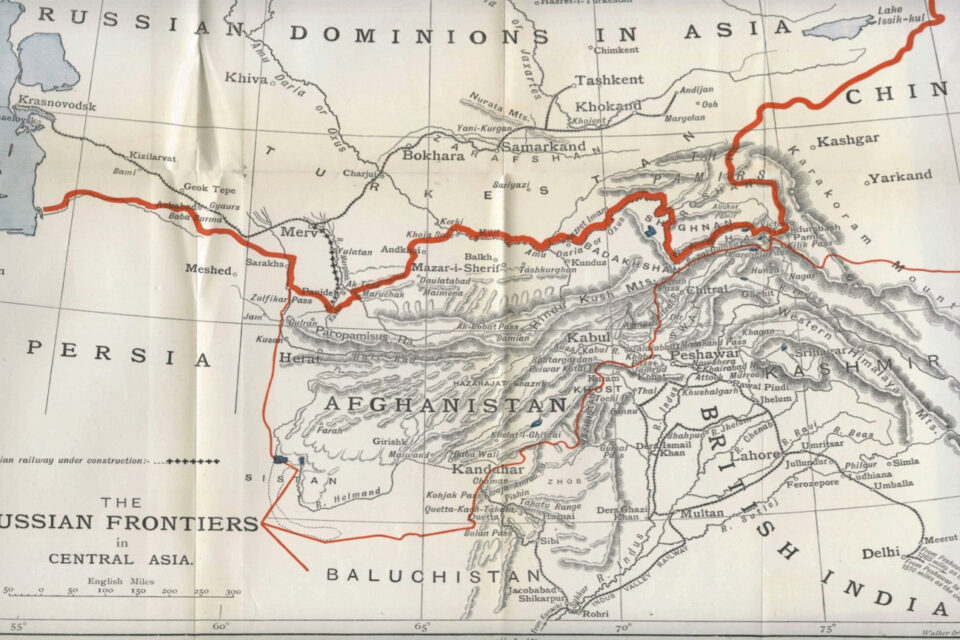

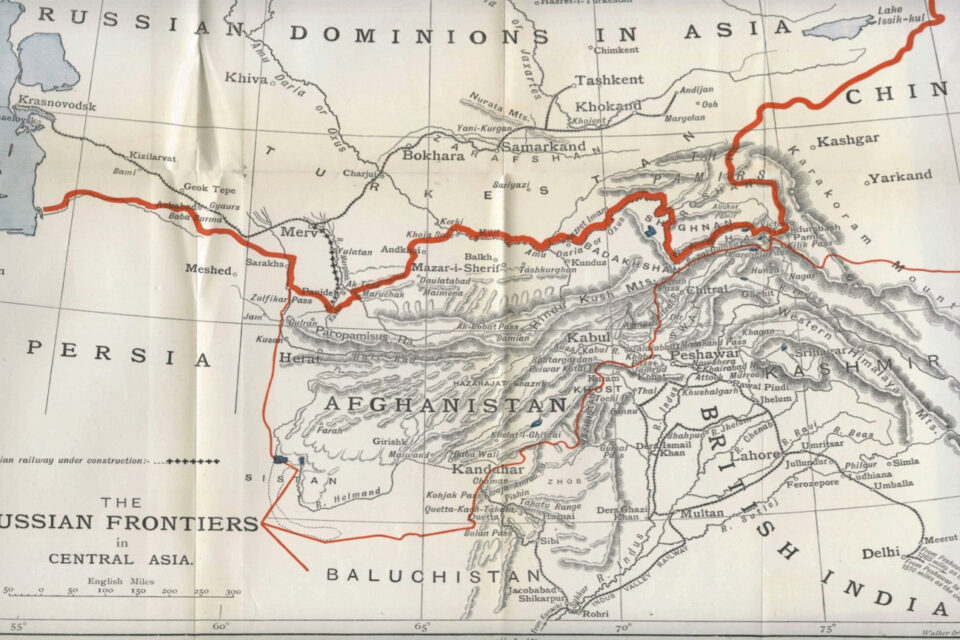

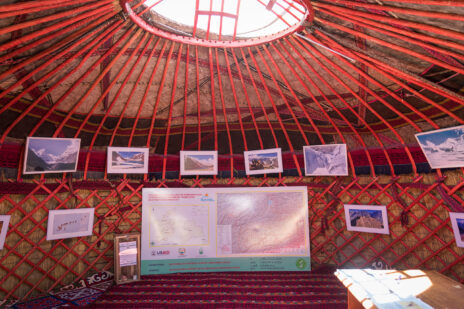

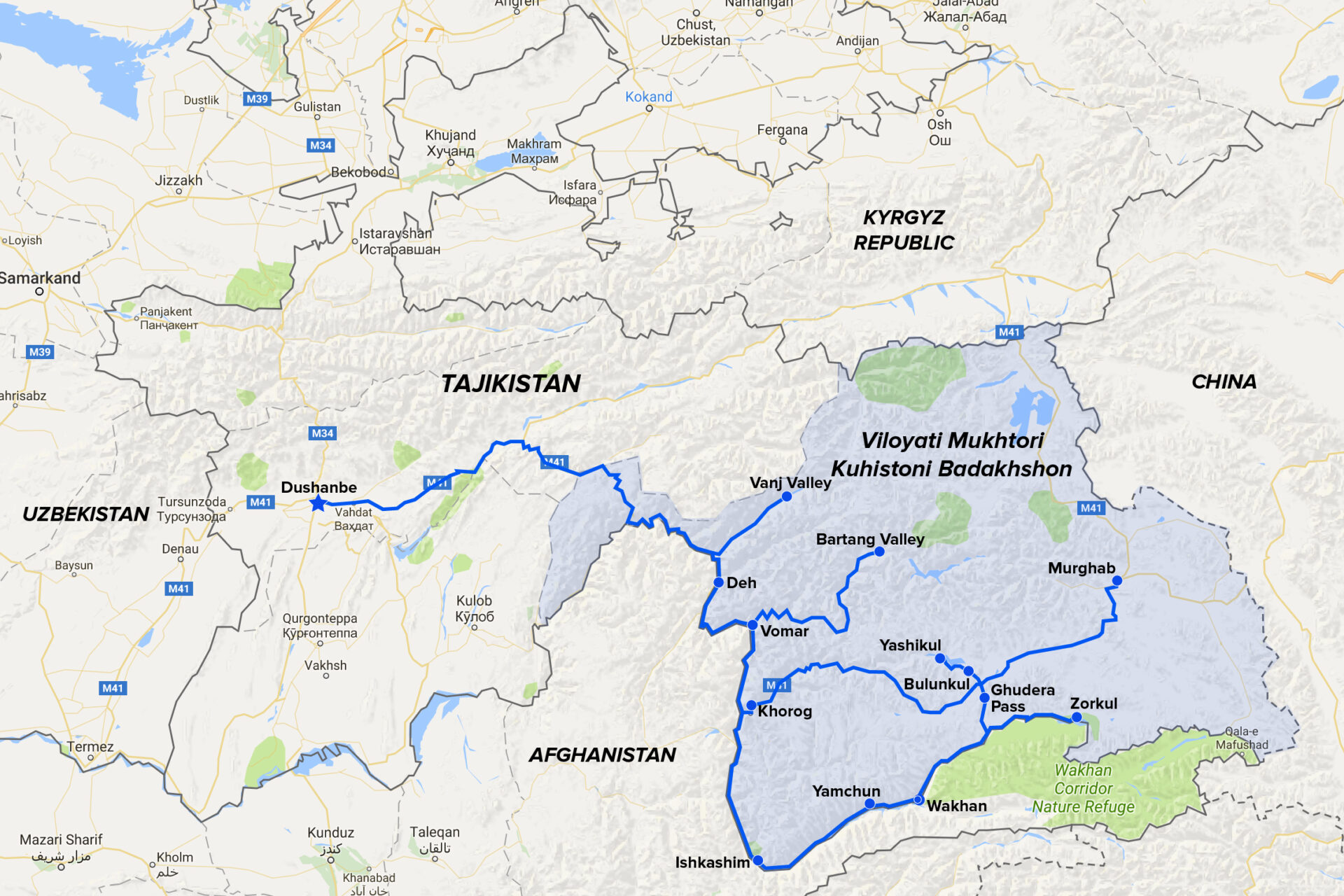

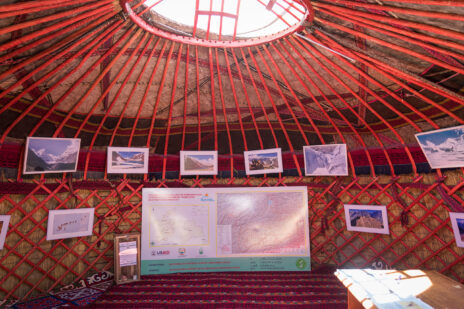

Standing in front of a large map of VMKB, Daler and I survey the Pamir Mountain range. Once home to the formidable warriors, the Scythians, the famous Silk Route traders, the Sogdians, and a key theatre of ‘The Great Game’, it is a region full of myth, intrigue and legend.

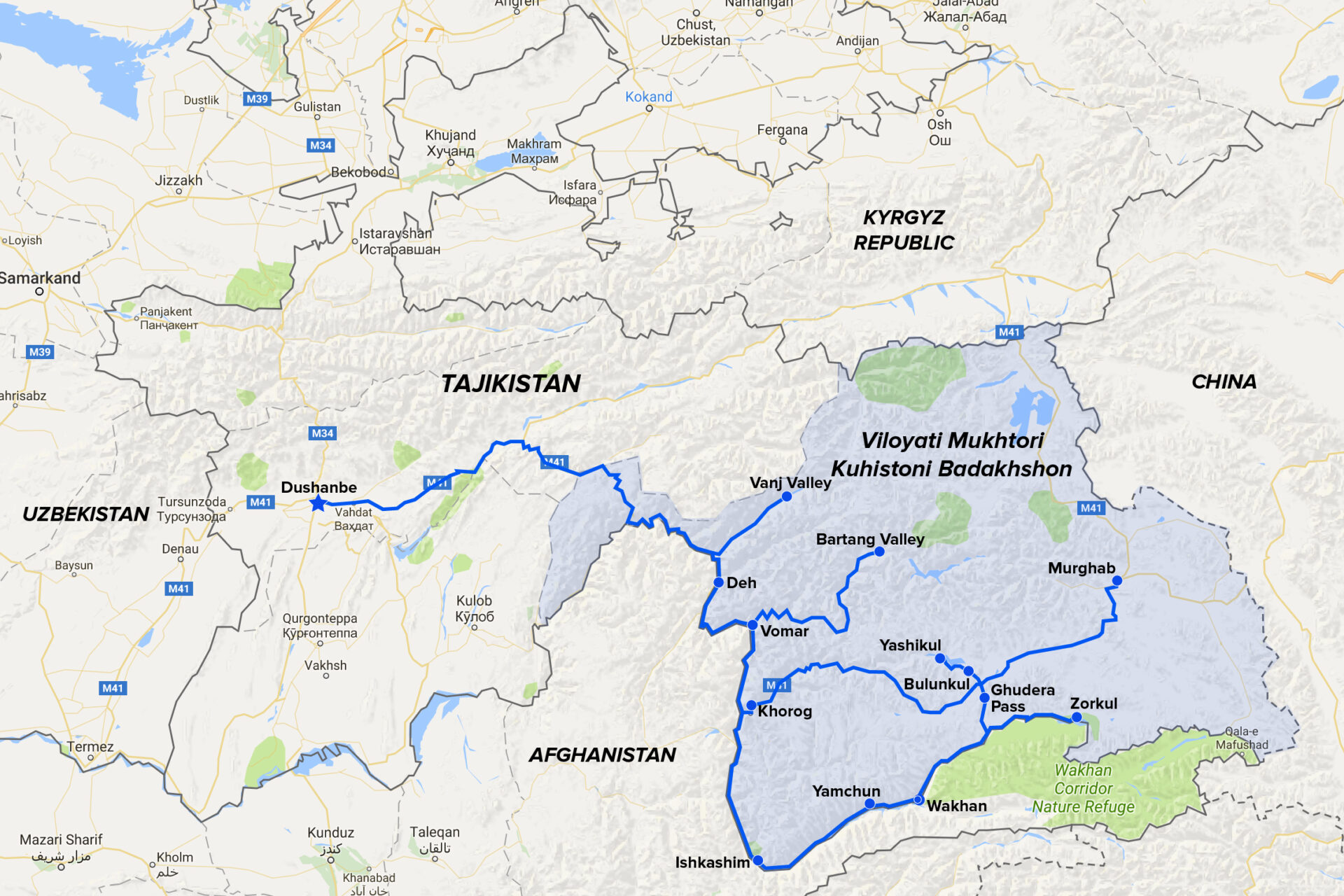

Standing in front of a huge map, Daler traces a route across the Pamirs, “you will visit places ninety-nine percent of people have never seen.”

His finger stops at Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the agents of the British Empire. “Here is the place where your people divided the Badakhshans and my people,” he says with a mischievous smile. “You must go. It is important that you understand your history.”

“Here is the place where your people divided my people”

THE ROAD TO MURGHAB

The following day we set off from Khorog – the main town of VMKB – at 4:30am. It’s a long way to Murghab, one of the most remote and, at 4,000 metres above sea level, one of the highest towns in Tajikistan.

After a few hours, we stop near Yashikul (‘the green lake’) where Pamir Energy has a regulating dam. This system ensures there is enough water flowing in the winter to drive turbines and generate the electricity needed to serve Pamir Energy’s customers. Two Pamir Energy staff live here in near isolation for shifts of 15 days after which they can return to their villages.

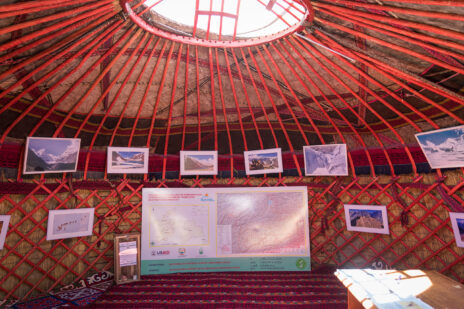

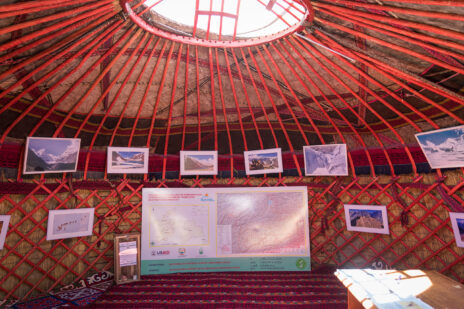

Before continuing eastward we stop off in nearby Bulunkul village to join a ceremony to mark the opening of a new tourism centre. A young Tajik girl performs a mesmerising dance to open the event. Locals, some wearing traditional clothing, have congregated to watch. Yak, horses and Bactrian camel graze nearby.

This centre is one part of AKDN and its partners’ broader efforts to attract tourism to the region and generate economic opportunities for locals. The US Ambassador and AKDN’s Resident Representative to Tajikistan are here to speak about their respective commitment to this endeavour and hope for the future. AKDN’s tourism promotion activities span centres like this one, hotels and the restoration of historic monuments. It is not inconceivable that one day this beautiful and relatively unknown part of the world could attract more than just the most adventurous of tourists.

After a lunch of typical Pamiri food – gartha (roundels of flat bread), kharvo (a vegetable soup with a piece of meat) and trout (introduced to the nearby lakes by the Soviets) – we continue on our way.

As we climb higher up and further eastward the landscape appears increasingly dusty and moon-like and vegetation becomes more sparse. Above 3,000 metres there are no longer any trees. The air is thin. A short walk from the car has me gasping for breath.

Unlike the rockier Pamirs to the west that burst out of the earth’s surface in dark browns and deep ochres, the mountains here are softer and glow purple, pink and blue. “The rockier the mountains, the younger they are,” my friend Dastanbui later tells me. The valleys too have become wider; at times vastly so.

“The rockier the mountains, the younger they are”

In the distance, we see Kyrgyz yurts at the base of snow capped peaks. The semi-nomadic herdsmen are here with their yak, making the most of the rich summer pastures. In winter they will return to Murghab town where they can stay warm.

Parallel to the road is an endless chain of telegraph poles. Not so long ago, they were the only communications link between Mughab and the outside world. Built by the Soviets in the 1950s, the poles still stand proudly for hundreds of kilometres even though their original use is long since past; unlike the road we race along, also Soviet-built.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union,” says Igor one of my travel companions. I understand his point. Schools, hospitals, roads, water works, energy and more: all were invested in by the Soviets even in this most remote corner of their empire. Across the the border in Afghanistan and beyond the Soviet sphere of influence, there is nothing like this. Barely a light can be seen at night; a situation Pamir Energy is working to address through its cross-border energy programme.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union”

As we enter the late afternoon, a wide and fertile valley opens before us. We are close to Murghab town and not far from the Chinese border; the primary reason for the town’s strategic importance to the Soviets.

Of the 6,000 people who live in Murghab town, most are semi-nomadic Kyrgyz people, the rest are Pamiri Tajiks. Our first stop is the site of Pamir Energy’s new 1.5MW hydropower plant that is due to open in June 2018.

As we arrive at the construction site, huge diggers and industrial machinery are preparing the way for the new turbines that will generate the district’s energy needs. After completion, this will take Pamir Energy’s coverage to 99% of VMKB. The few remaining unconnected valleys will follow soon after.

It’s easy to forget the impact electricity has on our lives. Imagine having to spend several hours each day collecting wood to heat your homes and to cook your food or having to hand wash your clothes. Imagine the lost time. Imagine not having the internet, or your phone or a TV. Imagine what you wouldn’t know.

This is why UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon has called sustainable energy, “the golden thread that connects economic growth, increased social equity and an environment that allows the world to thrive” and why Pamir Energy is investing in this essential catalyst to the development of human life.

MURGHAB TO ZORKUL

The following morning we head into the town centre where Kyrgyz men, with their distinctive Kalpak hats, and women greet one another on their morning stroll.

I meet a famous local embroiderer – Rahima – who has been supported by the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) to set up her business. Rahima now employs 10 women who clean wool, prepare the dyes and are learning the craft. Her pieces are sold in local markets and exhibited across Tajikistan. Across VMKB, AKF supports many female artisans like Rahima to start businesses and earn an independent income. Slowly, women like Rahima are helping reshape the role of women and their perceived value within their communities.

Back on the road we start a 300km leg south to Zorkul; the site Daler was so keen for me, a British man, to see. As the altitude decreases, the mountains become rockier and the valleys narrower. To my surprise we pass about 15 mountain bikers making the several hundred mile journey from Ishkashim to Murghab. The mind boggles.

A further four hours drive south, Afghanistan and its majestic snow-capped peaks come into view. To reach Zorkul we pass a military checkpoint. Being so close to the Afghan border we need to be accompanied by an armed guard.

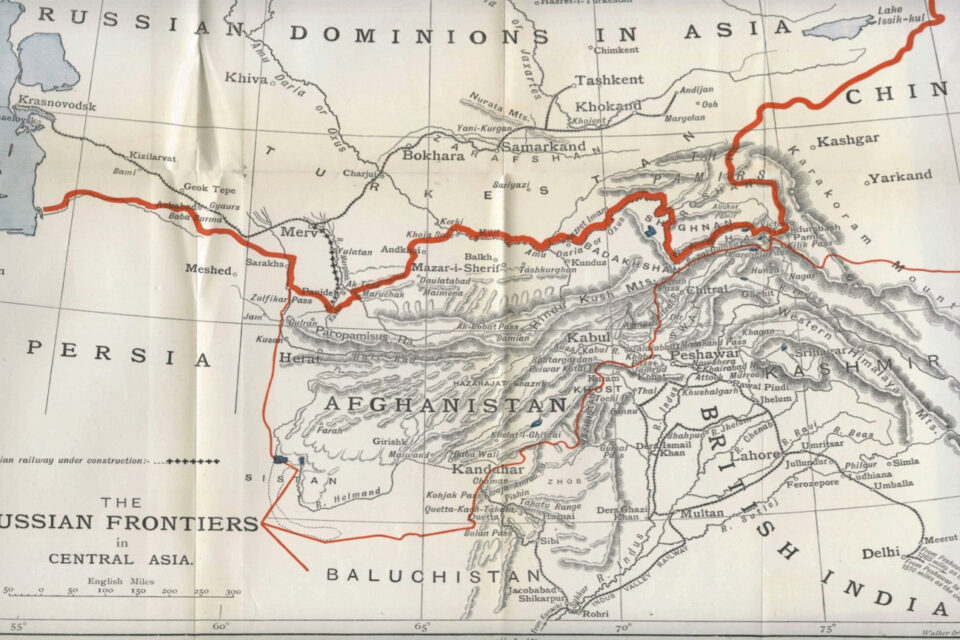

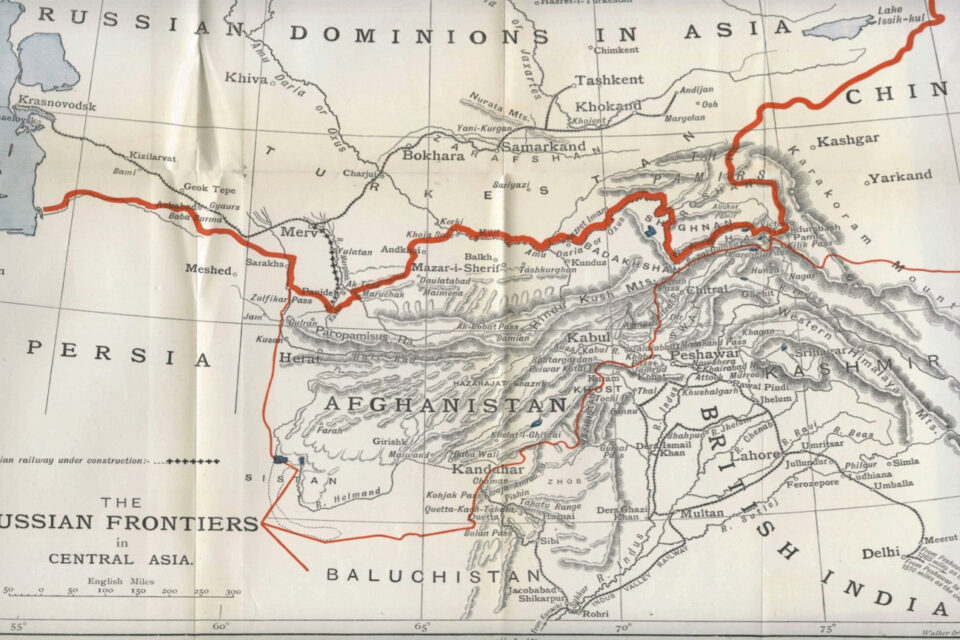

The road to Zorkul runs parallel with the Panj river which marks the Afghan-Tajik border. The river is so narrow at points you could jump over it into Afghanistan. Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the British, marks the spot where in 1895 the British and Russians signed the ‘Pamir Convention’; an agreement that ended years of suspicion and paranoia between the powers and formally demarcated their respective spheres of influence in Central Asia. Using the Panj river as their guide, the empires separated Badakhshan province into what would become Tajikistan and Afghanistan and sent these respective nations onto vastly different development trajectories; socially, cultural and economically. Families were separated and a people and culture divided.

THE WAKHAN CORRIDOR

To begin the loop back to Khorog we need to take the Ghudera pass; a frighteningly narrow road that clings to the edge of the steep mountains. After several hours driving, the valley floor opens out majestically into the Wakhan Corridor. The trees have returned.

We’re staying at a basic hotel near the hot springs of Bibi Fatima. “They have paper in the toilets, you don’t have to use rocks like Tajik men and womens,” giggles Igor. It is late and I am exhausted but I don’t want to miss the opportunity to visit the spring which Igor describes as “a mystical experience”. I am not disappointed. Sitting on a mountain face, in a pool of hot water high up in the Pamirs, it is awe-inspiring. We bathe a while, talk a little and enjoy this natural wonder.

The next day we set off back to Khorog via Ishkashim. We pass Zamr-i atish parast (Fortress of the Fire Worshippers) which sits majestically overlooking the Wahkan and the mountains of Afghanistan. This crumbling fortress, that dates back to the third century BCE, once guarded the trade route to the north of the river Panj. Not much remains although there is talk that it could be restored one day.

Closer to the river basin, farmers are harvesting fields that lie adjacent to the vast river basin. They grow wheat and potatoes; the latter this region is famous for.

Further north, we visit Deh; a village that has just started receiving electricity again after 20 years without it – since the fall of the Soviet Union. “It’s the first hot shower we have had in a long time,” the head of the village council tells me.

I meet Hamida who migrated to Russia in 2006 but has recently moved back to Deh with her family. I ask her why they have retuned. She tells me it is simple: “because the village has electricity now.” She elaborates: “I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children. Before I would have to spend all day collecting wood now there’s no need. We have TV so the kids can watch cartoons and we can watch the news. We’re more aware of what’s going on in the world. It’s good to be back.”

In the context of today’s migration crisis, this strikes me as significant. If families can live in peace and with access to basic services, like electricity, and opportunity many would never choose to leave in the first place.

“I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children”

THE LAST LEG

From Darvaz, our last stop, we make way for the capital Dushanbe; the final stretch of our 3,000km journey. The mighty mountains begin to recede and give way to gently undulating farmland. The remainder of the journey provides time for reflection.

Much has been and is being done by Pamir Energy, the Aga Khan Development Network, the international donor community and others to improve the living conditions of the people of the Pamirs and encourage inward investment. Great strides have been made in literacy and life expectancy.

The construction of new energy lines, bridges and markets are helping catalyse economic development and are reconnecting eastern Tajikistan with Northern Afghanistan once more allowing them to share in their limited resources, trade with each other, and prosper together. Ultimately, to support one another.

In many respects, these initiatives are working to undo some of the damage caused by the imperial policies that divided this region whilst making the most of its Soviet legacy. With sustained support, it is possible that this remote and often misunderstood corner of the world may again claim its place as the economic, social and cultural hub of Central Asia and thrive once more.

Words and photographs by Christopher Wilton-Steer

More information about visiting Tajikistan’s Pamir mountains can be found via the Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association website.

Bulunkul Булункул

A girl dances at the opening ceremony of a new tourism centre in the Pamir Mountains. As part of its economic development work, the Aga Khan Foundation supports sustainable tourism in the region through the Pamir Eco-Culture and Tourism Association.

Ishkoshim Ишкошим

PECTA creates job opportunities for local people and encourages the preservation of historical heritage, natural resources and wildlife while helping tourists to visit this remote and breathtakingly beautiful region. Seen here is Zamr-i-atash-Paras; once a Zoroastrian stronghold that guarded the Silk Road trading routes to the north of the river Panj.

Tajikistan from above

Some aerial shots of Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast and its magnificent landscapes. GBAO comprises the easter half of Tajikistan and is home to the Pamir Mountains, also known as ‘the roof of the world’.

Bulunkul

Eastern Tajikistan is a magnet for adventure cyclists many of whom travel along the Pamir Highway – the historic trade route that connects much of Central Asia – for hundreds of kilometres to Kazakhstan.

Local life on a journey through Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains

In the heart of Central Asia lie the dramatic Pamir Mountains; while the topography of this lofty region poses unique challenges to daily life, new initiatives have helped to bring fresh opportunities to some of Tajikistan’s remotest communities.

See Christopher Wilton-Steer’s photo essay in National Geographic.

Tajikistan-Afghanistan border area

Vanj cross-border bridge between Afghanistan, left of the river, and Tajikistan, right of the river. This is one of six bridges constructed by the Aga Khan Foundation and partners to help improve connectivity and economic opportunities between these historically linked regions. While the British and Russian empires that separated these regions have faded into history, their legacy endures.

3,000KM ACROSS THE ROOF OF THE WORLD | On assignment in Eastern Tajikistan

PAMIR ENERGY, KHOROG

I’m beckoned into Daler Jumaev’s office and offered a seat.

Daler is on a call with one of his engineers and is giving him some heat down the phone, his fists thumping his desk with each word. He’s speaking in Tajik but I think I understand the message: “I’m not interested in excuses. Get. It. Done.” I remember Daler once telling me, to get things done in Tajikistan, you need to be tough.

He hangs up, the momentary frustration has passed and he comes to greet me in that typical Daler way, with a huge grin and a bear hug. “Welcome Chris-tow-feerr! How was your flight?”

Daler Jumaev is the General Director of Pamir Energy; an off-grid energy company that owns and operates several small scale hydropower plants and a network of distribution lines spanning 4,300km across Viloyati Mukhtori Kuhistoni Badakhshon (VMKB); the eastern half of Tajikistan to you and me. Of the many hats Daler wears this is perhaps the most important one; over 250,000 people are relying on him to provide their electricity in this remote mountainous part of the world.

Daler has invited me to VMKB to photograph the Pamir Energy network and the people whose lives it touches. The company has a great story to tell.

Pamir Energy was established in 2002 to respond to the region’s dire energy needs that followed the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the ensuing civil war. At that time, only 13% of the population had access to electricity. Wood being the only readily available fuel, 70% of the region was deforested. Living standards and the quality of life declined dramatically throughout the 1990s.

This was the context in which the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), the Government of Tajikistan and the World Bank established Pamir Energy; Central Asia’s first public private partnership. It’s mission: to turn around a post-Soviet utility to provide clean and affordable energy 24 hours a day to the poor communities in the region.

Today, 96% of the population of VMKB are able to access energy; a remarkable achievement. In 2008 the company began to export electricity across the border to northern Afghanistan. Some villages are receiving electricity for the first time in their history.

Standing in front of a large map of VMKB, Daler and I survey the Pamir Mountain range. Once home to the formidable warriors, the Scythians, the famous Silk Route traders, the Sogdians, and a key theatre of ‘The Great Game’, it is a region full of myth, intrigue and legend.

Standing in front of a huge map, Daler traces a route across the Pamirs, “you will visit places ninety-nine percent of people have never seen.”

His finger stops at Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the agents of the British Empire. “Here is the place where your people divided the Badakhshans and my people,” he says with a mischievous smile. “You must go. It is important that you understand your history.”

“Here is the place where your people divided my people”

THE ROAD TO MURGHAB

The following day we set off from Khorog – the main town of VMKB – at 4:30am. It’s a long way to Murghab, one of the most remote and, at 4,000 metres above sea level, one of the highest towns in Tajikistan.

After a few hours, we stop near Yashikul (‘the green lake’) where Pamir Energy has a regulating dam. This system ensures there is enough water flowing in the winter to drive turbines and generate the electricity needed to serve Pamir Energy’s customers. Two Pamir Energy staff live here in near isolation for shifts of 15 days after which they can return to their villages.

Before continuing eastward we stop off in nearby Bulunkul village to join a ceremony to mark the opening of a new tourism centre. A young Tajik girl performs a mesmerising dance to open the event. Locals, some wearing traditional clothing, have congregated to watch. Yak, horses and Bactrian camel graze nearby.

This centre is one part of AKDN and its partners’ broader efforts to attract tourism to the region and generate economic opportunities for locals. The US Ambassador and AKDN’s Resident Representative to Tajikistan are here to speak about their respective commitment to this endeavour and hope for the future. AKDN’s tourism promotion activities span centres like this one, hotels and the restoration of historic monuments. It is not inconceivable that one day this beautiful and relatively unknown part of the world could attract more than just the most adventurous of tourists.

After a lunch of typical Pamiri food – gartha (roundels of flat bread), kharvo (a vegetable soup with a piece of meat) and trout (introduced to the nearby lakes by the Soviets) – we continue on our way.

As we climb higher up and further eastward the landscape appears increasingly dusty and moon-like and vegetation becomes more sparse. Above 3,000 metres there are no longer any trees. The air is thin. A short walk from the car has me gasping for breath.

Unlike the rockier Pamirs to the west that burst out of the earth’s surface in dark browns and deep ochres, the mountains here are softer and glow purple, pink and blue. “The rockier the mountains, the younger they are,” my friend Dastanbui later tells me. The valleys too have become wider; at times vastly so.

“The rockier the mountains, the younger they are”

In the distance, we see Kyrgyz yurts at the base of snow capped peaks. The semi-nomadic herdsmen are here with their yak, making the most of the rich summer pastures. In winter they will return to Murghab town where they can stay warm.

Parallel to the road is an endless chain of telegraph poles. Not so long ago, they were the only communications link between Mughab and the outside world. Built by the Soviets in the 1950s, the poles still stand proudly for hundreds of kilometres even though their original use is long since past; unlike the road we race along, also Soviet-built.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union,” says Igor one of my travel companions. I understand his point. Schools, hospitals, roads, water works, energy and more: all were invested in by the Soviets even in this most remote corner of their empire. Across the the border in Afghanistan and beyond the Soviet sphere of influence, there is nothing like this. Barely a light can be seen at night; a situation Pamir Energy is working to address through its cross-border energy programme.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union”

As we enter the late afternoon, a wide and fertile valley opens before us. We are close to Murghab town and not far from the Chinese border; the primary reason for the town’s strategic importance to the Soviets.

Of the 6,000 people who live in Murghab town, most are semi-nomadic Kyrgyz people, the rest are Pamiri Tajiks. Our first stop is the site of Pamir Energy’s new 1.5MW hydropower plant that is due to open in June 2018.

As we arrive at the construction site, huge diggers and industrial machinery are preparing the way for the new turbines that will generate the district’s energy needs. After completion, this will take Pamir Energy’s coverage to 99% of VMKB. The few remaining unconnected valleys will follow soon after.

It’s easy to forget the impact electricity has on our lives. Imagine having to spend several hours each day collecting wood to heat your homes and to cook your food or having to hand wash your clothes. Imagine the lost time. Imagine not having the internet, or your phone or a TV. Imagine what you wouldn’t know.

This is why UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon has called sustainable energy, “the golden thread that connects economic growth, increased social equity and an environment that allows the world to thrive” and why Pamir Energy is investing in this essential catalyst to the development of human life.

MURGHAB TO ZORKUL

The following morning we head into the town centre where Kyrgyz men, with their distinctive Kalpak hats, and women greet one another on their morning stroll.

I meet a famous local embroiderer – Rahima – who has been supported by the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) to set up her business. Rahima now employs 10 women who clean wool, prepare the dyes and are learning the craft. Her pieces are sold in local markets and exhibited across Tajikistan. Across VMKB, AKF supports many female artisans like Rahima to start businesses and earn an independent income. Slowly, women like Rahima are helping reshape the role of women and their perceived value within their communities.

Back on the road we start a 300km leg south to Zorkul; the site Daler was so keen for me, a British man, to see. As the altitude decreases, the mountains become rockier and the valleys narrower. To my surprise we pass about 15 mountain bikers making the several hundred mile journey from Ishkashim to Murghab. The mind boggles.

A further four hours drive south, Afghanistan and its majestic snow-capped peaks come into view. To reach Zorkul we pass a military checkpoint. Being so close to the Afghan border we need to be accompanied by an armed guard.

The road to Zorkul runs parallel with the Panj river which marks the Afghan-Tajik border. The river is so narrow at points you could jump over it into Afghanistan. Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the British, marks the spot where in 1895 the British and Russians signed the ‘Pamir Convention’; an agreement that ended years of suspicion and paranoia between the powers and formally demarcated their respective spheres of influence in Central Asia. Using the Panj river as their guide, the empires separated Badakhshan province into what would become Tajikistan and Afghanistan and sent these respective nations onto vastly different development trajectories; socially, cultural and economically. Families were separated and a people and culture divided.

THE WAKHAN CORRIDOR

To begin the loop back to Khorog we need to take the Ghudera pass; a frighteningly narrow road that clings to the edge of the steep mountains. After several hours driving, the valley floor opens out majestically into the Wakhan Corridor. The trees have returned.

We’re staying at a basic hotel near the hot springs of Bibi Fatima. “They have paper in the toilets, you don’t have to use rocks like Tajik men and womens,” giggles Igor. It is late and I am exhausted but I don’t want to miss the opportunity to visit the spring which Igor describes as “a mystical experience”. I am not disappointed. Sitting on a mountain face, in a pool of hot water high up in the Pamirs, it is awe-inspiring. We bathe a while, talk a little and enjoy this natural wonder.

The next day we set off back to Khorog via Ishkashim. We pass Zamr-i atish parast (Fortress of the Fire Worshippers) which sits majestically overlooking the Wahkan and the mountains of Afghanistan. This crumbling fortress, that dates back to the third century BCE, once guarded the trade route to the north of the river Panj. Not much remains although there is talk that it could be restored one day.

Closer to the river basin, farmers are harvesting fields that lie adjacent to the vast river basin. They grow wheat and potatoes; the latter this region is famous for.

Further north, we visit Deh; a village that has just started receiving electricity again after 20 years without it – since the fall of the Soviet Union. “It’s the first hot shower we have had in a long time,” the head of the village council tells me.

I meet Hamida who migrated to Russia in 2006 but has recently moved back to Deh with her family. I ask her why they have retuned. She tells me it is simple: “because the village has electricity now.” She elaborates: “I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children. Before I would have to spend all day collecting wood now there’s no need. We have TV so the kids can watch cartoons and we can watch the news. We’re more aware of what’s going on in the world. It’s good to be back.”

In the context of today’s migration crisis, this strikes me as significant. If families can live in peace and with access to basic services, like electricity, and opportunity many would never choose to leave in the first place.

“I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children”

THE LAST LEG

From Darvaz, our last stop, we make way for the capital Dushanbe; the final stretch of our 3,000km journey. The mighty mountains begin to recede and give way to gently undulating farmland. The remainder of the journey provides time for reflection.

Much has been and is being done by Pamir Energy, the Aga Khan Development Network, the international donor community and others to improve the living conditions of the people of the Pamirs and encourage inward investment. Great strides have been made in literacy and life expectancy.

The construction of new energy lines, bridges and markets are helping catalyse economic development and are reconnecting eastern Tajikistan with Northern Afghanistan once more allowing them to share in their limited resources, trade with each other, and prosper together. Ultimately, to support one another.

In many respects, these initiatives are working to undo some of the damage caused by the imperial policies that divided this region whilst making the most of its Soviet legacy. With sustained support, it is possible that this remote and often misunderstood corner of the world may again claim its place as the economic, social and cultural hub of Central Asia and thrive once more.

Words and photographs by Christopher Wilton-Steer

More information about visiting Tajikistan’s Pamir mountains can be found via the Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association website.

Tajikistan-Afghanistan border area минтақаи сарҳадӣ Тоҷикистон Афғонистон

Thanks to investment during the Soviet period, Tajiks enjoy far greater access to education, healthcare and economic opportunities compared to their Afghan neighbours. Today, agreements between the Tajik and Afghan governments allow for more cooperation than has been possible for over a century. Traders are able to sell goods in specially designated markets near these bridges opening new economic opportunities.

3,000KM ACROSS THE ROOF OF THE WORLD | On assignment in Eastern Tajikistan

PAMIR ENERGY, KHOROG

I’m beckoned into Daler Jumaev’s office and offered a seat.

Daler is on a call with one of his engineers and is giving him some heat down the phone, his fists thumping his desk with each word. He’s speaking in Tajik but I think I understand the message: “I’m not interested in excuses. Get. It. Done.” I remember Daler once telling me, to get things done in Tajikistan, you need to be tough.

He hangs up, the momentary frustration has passed and he comes to greet me in that typical Daler way, with a huge grin and a bear hug. “Welcome Chris-tow-feerr! How was your flight?”

Daler Jumaev is the General Director of Pamir Energy; an off-grid energy company that owns and operates several small scale hydropower plants and a network of distribution lines spanning 4,300km across Viloyati Mukhtori Kuhistoni Badakhshon (VMKB); the eastern half of Tajikistan to you and me. Of the many hats Daler wears this is perhaps the most important one; over 250,000 people are relying on him to provide their electricity in this remote mountainous part of the world.

Daler has invited me to VMKB to photograph the Pamir Energy network and the people whose lives it touches. The company has a great story to tell.

Pamir Energy was established in 2002 to respond to the region’s dire energy needs that followed the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the ensuing civil war. At that time, only 13% of the population had access to electricity. Wood being the only readily available fuel, 70% of the region was deforested. Living standards and the quality of life declined dramatically throughout the 1990s.

This was the context in which the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), the Government of Tajikistan and the World Bank established Pamir Energy; Central Asia’s first public private partnership. It’s mission: to turn around a post-Soviet utility to provide clean and affordable energy 24 hours a day to the poor communities in the region.

Today, 96% of the population of VMKB are able to access energy; a remarkable achievement. In 2008 the company began to export electricity across the border to northern Afghanistan. Some villages are receiving electricity for the first time in their history.

Standing in front of a large map of VMKB, Daler and I survey the Pamir Mountain range. Once home to the formidable warriors, the Scythians, the famous Silk Route traders, the Sogdians, and a key theatre of ‘The Great Game’, it is a region full of myth, intrigue and legend.

Standing in front of a huge map, Daler traces a route across the Pamirs, “you will visit places ninety-nine percent of people have never seen.”

His finger stops at Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the agents of the British Empire. “Here is the place where your people divided the Badakhshans and my people,” he says with a mischievous smile. “You must go. It is important that you understand your history.”

“Here is the place where your people divided my people”

THE ROAD TO MURGHAB

The following day we set off from Khorog – the main town of VMKB – at 4:30am. It’s a long way to Murghab, one of the most remote and, at 4,000 metres above sea level, one of the highest towns in Tajikistan.

After a few hours, we stop near Yashikul (‘the green lake’) where Pamir Energy has a regulating dam. This system ensures there is enough water flowing in the winter to drive turbines and generate the electricity needed to serve Pamir Energy’s customers. Two Pamir Energy staff live here in near isolation for shifts of 15 days after which they can return to their villages.

Before continuing eastward we stop off in nearby Bulunkul village to join a ceremony to mark the opening of a new tourism centre. A young Tajik girl performs a mesmerising dance to open the event. Locals, some wearing traditional clothing, have congregated to watch. Yak, horses and Bactrian camel graze nearby.

This centre is one part of AKDN and its partners’ broader efforts to attract tourism to the region and generate economic opportunities for locals. The US Ambassador and AKDN’s Resident Representative to Tajikistan are here to speak about their respective commitment to this endeavour and hope for the future. AKDN’s tourism promotion activities span centres like this one, hotels and the restoration of historic monuments. It is not inconceivable that one day this beautiful and relatively unknown part of the world could attract more than just the most adventurous of tourists.

After a lunch of typical Pamiri food – gartha (roundels of flat bread), kharvo (a vegetable soup with a piece of meat) and trout (introduced to the nearby lakes by the Soviets) – we continue on our way.

As we climb higher up and further eastward the landscape appears increasingly dusty and moon-like and vegetation becomes more sparse. Above 3,000 metres there are no longer any trees. The air is thin. A short walk from the car has me gasping for breath.

Unlike the rockier Pamirs to the west that burst out of the earth’s surface in dark browns and deep ochres, the mountains here are softer and glow purple, pink and blue. “The rockier the mountains, the younger they are,” my friend Dastanbui later tells me. The valleys too have become wider; at times vastly so.

“The rockier the mountains, the younger they are”

In the distance, we see Kyrgyz yurts at the base of snow capped peaks. The semi-nomadic herdsmen are here with their yak, making the most of the rich summer pastures. In winter they will return to Murghab town where they can stay warm.

Parallel to the road is an endless chain of telegraph poles. Not so long ago, they were the only communications link between Mughab and the outside world. Built by the Soviets in the 1950s, the poles still stand proudly for hundreds of kilometres even though their original use is long since past; unlike the road we race along, also Soviet-built.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union,” says Igor one of my travel companions. I understand his point. Schools, hospitals, roads, water works, energy and more: all were invested in by the Soviets even in this most remote corner of their empire. Across the the border in Afghanistan and beyond the Soviet sphere of influence, there is nothing like this. Barely a light can be seen at night; a situation Pamir Energy is working to address through its cross-border energy programme.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union”

As we enter the late afternoon, a wide and fertile valley opens before us. We are close to Murghab town and not far from the Chinese border; the primary reason for the town’s strategic importance to the Soviets.

Of the 6,000 people who live in Murghab town, most are semi-nomadic Kyrgyz people, the rest are Pamiri Tajiks. Our first stop is the site of Pamir Energy’s new 1.5MW hydropower plant that is due to open in June 2018.

As we arrive at the construction site, huge diggers and industrial machinery are preparing the way for the new turbines that will generate the district’s energy needs. After completion, this will take Pamir Energy’s coverage to 99% of VMKB. The few remaining unconnected valleys will follow soon after.

It’s easy to forget the impact electricity has on our lives. Imagine having to spend several hours each day collecting wood to heat your homes and to cook your food or having to hand wash your clothes. Imagine the lost time. Imagine not having the internet, or your phone or a TV. Imagine what you wouldn’t know.

This is why UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon has called sustainable energy, “the golden thread that connects economic growth, increased social equity and an environment that allows the world to thrive” and why Pamir Energy is investing in this essential catalyst to the development of human life.

MURGHAB TO ZORKUL

The following morning we head into the town centre where Kyrgyz men, with their distinctive Kalpak hats, and women greet one another on their morning stroll.

I meet a famous local embroiderer – Rahima – who has been supported by the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) to set up her business. Rahima now employs 10 women who clean wool, prepare the dyes and are learning the craft. Her pieces are sold in local markets and exhibited across Tajikistan. Across VMKB, AKF supports many female artisans like Rahima to start businesses and earn an independent income. Slowly, women like Rahima are helping reshape the role of women and their perceived value within their communities.

Back on the road we start a 300km leg south to Zorkul; the site Daler was so keen for me, a British man, to see. As the altitude decreases, the mountains become rockier and the valleys narrower. To my surprise we pass about 15 mountain bikers making the several hundred mile journey from Ishkashim to Murghab. The mind boggles.

A further four hours drive south, Afghanistan and its majestic snow-capped peaks come into view. To reach Zorkul we pass a military checkpoint. Being so close to the Afghan border we need to be accompanied by an armed guard.

The road to Zorkul runs parallel with the Panj river which marks the Afghan-Tajik border. The river is so narrow at points you could jump over it into Afghanistan. Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the British, marks the spot where in 1895 the British and Russians signed the ‘Pamir Convention’; an agreement that ended years of suspicion and paranoia between the powers and formally demarcated their respective spheres of influence in Central Asia. Using the Panj river as their guide, the empires separated Badakhshan province into what would become Tajikistan and Afghanistan and sent these respective nations onto vastly different development trajectories; socially, cultural and economically. Families were separated and a people and culture divided.

THE WAKHAN CORRIDOR

To begin the loop back to Khorog we need to take the Ghudera pass; a frighteningly narrow road that clings to the edge of the steep mountains. After several hours driving, the valley floor opens out majestically into the Wakhan Corridor. The trees have returned.

We’re staying at a basic hotel near the hot springs of Bibi Fatima. “They have paper in the toilets, you don’t have to use rocks like Tajik men and womens,” giggles Igor. It is late and I am exhausted but I don’t want to miss the opportunity to visit the spring which Igor describes as “a mystical experience”. I am not disappointed. Sitting on a mountain face, in a pool of hot water high up in the Pamirs, it is awe-inspiring. We bathe a while, talk a little and enjoy this natural wonder.

The next day we set off back to Khorog via Ishkashim. We pass Zamr-i atish parast (Fortress of the Fire Worshippers) which sits majestically overlooking the Wahkan and the mountains of Afghanistan. This crumbling fortress, that dates back to the third century BCE, once guarded the trade route to the north of the river Panj. Not much remains although there is talk that it could be restored one day.

Closer to the river basin, farmers are harvesting fields that lie adjacent to the vast river basin. They grow wheat and potatoes; the latter this region is famous for.

Further north, we visit Deh; a village that has just started receiving electricity again after 20 years without it – since the fall of the Soviet Union. “It’s the first hot shower we have had in a long time,” the head of the village council tells me.

I meet Hamida who migrated to Russia in 2006 but has recently moved back to Deh with her family. I ask her why they have retuned. She tells me it is simple: “because the village has electricity now.” She elaborates: “I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children. Before I would have to spend all day collecting wood now there’s no need. We have TV so the kids can watch cartoons and we can watch the news. We’re more aware of what’s going on in the world. It’s good to be back.”

In the context of today’s migration crisis, this strikes me as significant. If families can live in peace and with access to basic services, like electricity, and opportunity many would never choose to leave in the first place.

“I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children”

THE LAST LEG

From Darvaz, our last stop, we make way for the capital Dushanbe; the final stretch of our 3,000km journey. The mighty mountains begin to recede and give way to gently undulating farmland. The remainder of the journey provides time for reflection.

Much has been and is being done by Pamir Energy, the Aga Khan Development Network, the international donor community and others to improve the living conditions of the people of the Pamirs and encourage inward investment. Great strides have been made in literacy and life expectancy.

The construction of new energy lines, bridges and markets are helping catalyse economic development and are reconnecting eastern Tajikistan with Northern Afghanistan once more allowing them to share in their limited resources, trade with each other, and prosper together. Ultimately, to support one another.

In many respects, these initiatives are working to undo some of the damage caused by the imperial policies that divided this region whilst making the most of its Soviet legacy. With sustained support, it is possible that this remote and often misunderstood corner of the world may again claim its place as the economic, social and cultural hub of Central Asia and thrive once more.

Words and photographs by Christopher Wilton-Steer

More information about visiting Tajikistan’s Pamir mountains can be found via the Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association website.

Tajikistan-Afghanistan border area минтақаи сарҳадӣ Тоҷикистон Афғонистон

Supported by Aga Khan Health Services, Afghans can cross the bridges to gain access to critical healthcare saving them a two-day journey on hazardous mountain roads to the nearest Afghan hospital.

3,000KM ACROSS THE ROOF OF THE WORLD | On assignment in Eastern Tajikistan

PAMIR ENERGY, KHOROG

I’m beckoned into Daler Jumaev’s office and offered a seat.

Daler is on a call with one of his engineers and is giving him some heat down the phone, his fists thumping his desk with each word. He’s speaking in Tajik but I think I understand the message: “I’m not interested in excuses. Get. It. Done.” I remember Daler once telling me, to get things done in Tajikistan, you need to be tough.

He hangs up, the momentary frustration has passed and he comes to greet me in that typical Daler way, with a huge grin and a bear hug. “Welcome Chris-tow-feerr! How was your flight?”

Daler Jumaev is the General Director of Pamir Energy; an off-grid energy company that owns and operates several small scale hydropower plants and a network of distribution lines spanning 4,300km across Viloyati Mukhtori Kuhistoni Badakhshon (VMKB); the eastern half of Tajikistan to you and me. Of the many hats Daler wears this is perhaps the most important one; over 250,000 people are relying on him to provide their electricity in this remote mountainous part of the world.

Daler has invited me to VMKB to photograph the Pamir Energy network and the people whose lives it touches. The company has a great story to tell.

Pamir Energy was established in 2002 to respond to the region’s dire energy needs that followed the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the ensuing civil war. At that time, only 13% of the population had access to electricity. Wood being the only readily available fuel, 70% of the region was deforested. Living standards and the quality of life declined dramatically throughout the 1990s.

This was the context in which the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), the Government of Tajikistan and the World Bank established Pamir Energy; Central Asia’s first public private partnership. It’s mission: to turn around a post-Soviet utility to provide clean and affordable energy 24 hours a day to the poor communities in the region.

Today, 96% of the population of VMKB are able to access energy; a remarkable achievement. In 2008 the company began to export electricity across the border to northern Afghanistan. Some villages are receiving electricity for the first time in their history.

Standing in front of a large map of VMKB, Daler and I survey the Pamir Mountain range. Once home to the formidable warriors, the Scythians, the famous Silk Route traders, the Sogdians, and a key theatre of ‘The Great Game’, it is a region full of myth, intrigue and legend.

Standing in front of a huge map, Daler traces a route across the Pamirs, “you will visit places ninety-nine percent of people have never seen.”

His finger stops at Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the agents of the British Empire. “Here is the place where your people divided the Badakhshans and my people,” he says with a mischievous smile. “You must go. It is important that you understand your history.”

“Here is the place where your people divided my people”

THE ROAD TO MURGHAB

The following day we set off from Khorog – the main town of VMKB – at 4:30am. It’s a long way to Murghab, one of the most remote and, at 4,000 metres above sea level, one of the highest towns in Tajikistan.

After a few hours, we stop near Yashikul (‘the green lake’) where Pamir Energy has a regulating dam. This system ensures there is enough water flowing in the winter to drive turbines and generate the electricity needed to serve Pamir Energy’s customers. Two Pamir Energy staff live here in near isolation for shifts of 15 days after which they can return to their villages.

Before continuing eastward we stop off in nearby Bulunkul village to join a ceremony to mark the opening of a new tourism centre. A young Tajik girl performs a mesmerising dance to open the event. Locals, some wearing traditional clothing, have congregated to watch. Yak, horses and Bactrian camel graze nearby.

This centre is one part of AKDN and its partners’ broader efforts to attract tourism to the region and generate economic opportunities for locals. The US Ambassador and AKDN’s Resident Representative to Tajikistan are here to speak about their respective commitment to this endeavour and hope for the future. AKDN’s tourism promotion activities span centres like this one, hotels and the restoration of historic monuments. It is not inconceivable that one day this beautiful and relatively unknown part of the world could attract more than just the most adventurous of tourists.

After a lunch of typical Pamiri food – gartha (roundels of flat bread), kharvo (a vegetable soup with a piece of meat) and trout (introduced to the nearby lakes by the Soviets) – we continue on our way.

As we climb higher up and further eastward the landscape appears increasingly dusty and moon-like and vegetation becomes more sparse. Above 3,000 metres there are no longer any trees. The air is thin. A short walk from the car has me gasping for breath.

Unlike the rockier Pamirs to the west that burst out of the earth’s surface in dark browns and deep ochres, the mountains here are softer and glow purple, pink and blue. “The rockier the mountains, the younger they are,” my friend Dastanbui later tells me. The valleys too have become wider; at times vastly so.

“The rockier the mountains, the younger they are”

In the distance, we see Kyrgyz yurts at the base of snow capped peaks. The semi-nomadic herdsmen are here with their yak, making the most of the rich summer pastures. In winter they will return to Murghab town where they can stay warm.

Parallel to the road is an endless chain of telegraph poles. Not so long ago, they were the only communications link between Mughab and the outside world. Built by the Soviets in the 1950s, the poles still stand proudly for hundreds of kilometres even though their original use is long since past; unlike the road we race along, also Soviet-built.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union,” says Igor one of my travel companions. I understand his point. Schools, hospitals, roads, water works, energy and more: all were invested in by the Soviets even in this most remote corner of their empire. Across the the border in Afghanistan and beyond the Soviet sphere of influence, there is nothing like this. Barely a light can be seen at night; a situation Pamir Energy is working to address through its cross-border energy programme.

“Everything good about Tajikistan came from the Soviet Union”

As we enter the late afternoon, a wide and fertile valley opens before us. We are close to Murghab town and not far from the Chinese border; the primary reason for the town’s strategic importance to the Soviets.

Of the 6,000 people who live in Murghab town, most are semi-nomadic Kyrgyz people, the rest are Pamiri Tajiks. Our first stop is the site of Pamir Energy’s new 1.5MW hydropower plant that is due to open in June 2018.

As we arrive at the construction site, huge diggers and industrial machinery are preparing the way for the new turbines that will generate the district’s energy needs. After completion, this will take Pamir Energy’s coverage to 99% of VMKB. The few remaining unconnected valleys will follow soon after.

It’s easy to forget the impact electricity has on our lives. Imagine having to spend several hours each day collecting wood to heat your homes and to cook your food or having to hand wash your clothes. Imagine the lost time. Imagine not having the internet, or your phone or a TV. Imagine what you wouldn’t know.

This is why UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon has called sustainable energy, “the golden thread that connects economic growth, increased social equity and an environment that allows the world to thrive” and why Pamir Energy is investing in this essential catalyst to the development of human life.

MURGHAB TO ZORKUL

The following morning we head into the town centre where Kyrgyz men, with their distinctive Kalpak hats, and women greet one another on their morning stroll.

I meet a famous local embroiderer – Rahima – who has been supported by the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) to set up her business. Rahima now employs 10 women who clean wool, prepare the dyes and are learning the craft. Her pieces are sold in local markets and exhibited across Tajikistan. Across VMKB, AKF supports many female artisans like Rahima to start businesses and earn an independent income. Slowly, women like Rahima are helping reshape the role of women and their perceived value within their communities.

Back on the road we start a 300km leg south to Zorkul; the site Daler was so keen for me, a British man, to see. As the altitude decreases, the mountains become rockier and the valleys narrower. To my surprise we pass about 15 mountain bikers making the several hundred mile journey from Ishkashim to Murghab. The mind boggles.

A further four hours drive south, Afghanistan and its majestic snow-capped peaks come into view. To reach Zorkul we pass a military checkpoint. Being so close to the Afghan border we need to be accompanied by an armed guard.

The road to Zorkul runs parallel with the Panj river which marks the Afghan-Tajik border. The river is so narrow at points you could jump over it into Afghanistan. Zorkul, named Lake Victoria by the British, marks the spot where in 1895 the British and Russians signed the ‘Pamir Convention’; an agreement that ended years of suspicion and paranoia between the powers and formally demarcated their respective spheres of influence in Central Asia. Using the Panj river as their guide, the empires separated Badakhshan province into what would become Tajikistan and Afghanistan and sent these respective nations onto vastly different development trajectories; socially, cultural and economically. Families were separated and a people and culture divided.

THE WAKHAN CORRIDOR

To begin the loop back to Khorog we need to take the Ghudera pass; a frighteningly narrow road that clings to the edge of the steep mountains. After several hours driving, the valley floor opens out majestically into the Wakhan Corridor. The trees have returned.

We’re staying at a basic hotel near the hot springs of Bibi Fatima. “They have paper in the toilets, you don’t have to use rocks like Tajik men and womens,” giggles Igor. It is late and I am exhausted but I don’t want to miss the opportunity to visit the spring which Igor describes as “a mystical experience”. I am not disappointed. Sitting on a mountain face, in a pool of hot water high up in the Pamirs, it is awe-inspiring. We bathe a while, talk a little and enjoy this natural wonder.

The next day we set off back to Khorog via Ishkashim. We pass Zamr-i atish parast (Fortress of the Fire Worshippers) which sits majestically overlooking the Wahkan and the mountains of Afghanistan. This crumbling fortress, that dates back to the third century BCE, once guarded the trade route to the north of the river Panj. Not much remains although there is talk that it could be restored one day.

Closer to the river basin, farmers are harvesting fields that lie adjacent to the vast river basin. They grow wheat and potatoes; the latter this region is famous for.

Further north, we visit Deh; a village that has just started receiving electricity again after 20 years without it – since the fall of the Soviet Union. “It’s the first hot shower we have had in a long time,” the head of the village council tells me.

I meet Hamida who migrated to Russia in 2006 but has recently moved back to Deh with her family. I ask her why they have retuned. She tells me it is simple: “because the village has electricity now.” She elaborates: “I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children. Before I would have to spend all day collecting wood now there’s no need. We have TV so the kids can watch cartoons and we can watch the news. We’re more aware of what’s going on in the world. It’s good to be back.”

In the context of today’s migration crisis, this strikes me as significant. If families can live in peace and with access to basic services, like electricity, and opportunity many would never choose to leave in the first place.

“I used to have to wash clothes with my hands, now it’s 30 minutes in a washing machine so I have lots of time to do other things like spend time with the children”

THE LAST LEG

From Darvaz, our last stop, we make way for the capital Dushanbe; the final stretch of our 3,000km journey. The mighty mountains begin to recede and give way to gently undulating farmland. The remainder of the journey provides time for reflection.

Much has been and is being done by Pamir Energy, the Aga Khan Development Network, the international donor community and others to improve the living conditions of the people of the Pamirs and encourage inward investment. Great strides have been made in literacy and life expectancy.

The construction of new energy lines, bridges and markets are helping catalyse economic development and are reconnecting eastern Tajikistan with Northern Afghanistan once more allowing them to share in their limited resources, trade with each other, and prosper together. Ultimately, to support one another.

In many respects, these initiatives are working to undo some of the damage caused by the imperial policies that divided this region whilst making the most of its Soviet legacy. With sustained support, it is possible that this remote and often misunderstood corner of the world may again claim its place as the economic, social and cultural hub of Central Asia and thrive once more.

Words and photographs by Christopher Wilton-Steer

More information about visiting Tajikistan’s Pamir mountains can be found via the Pamir Eco-Cultural Tourism Association website.