The Silk Road

In 138 BCE, General Zhang Qian of China’s Han Dynasty was sent on a diplomatic mission to develop economic and cultural links with the peoples of Central Asia. In so doing, he set in motion the creation of a transcontinental trade route that would shape the world as we know it today.

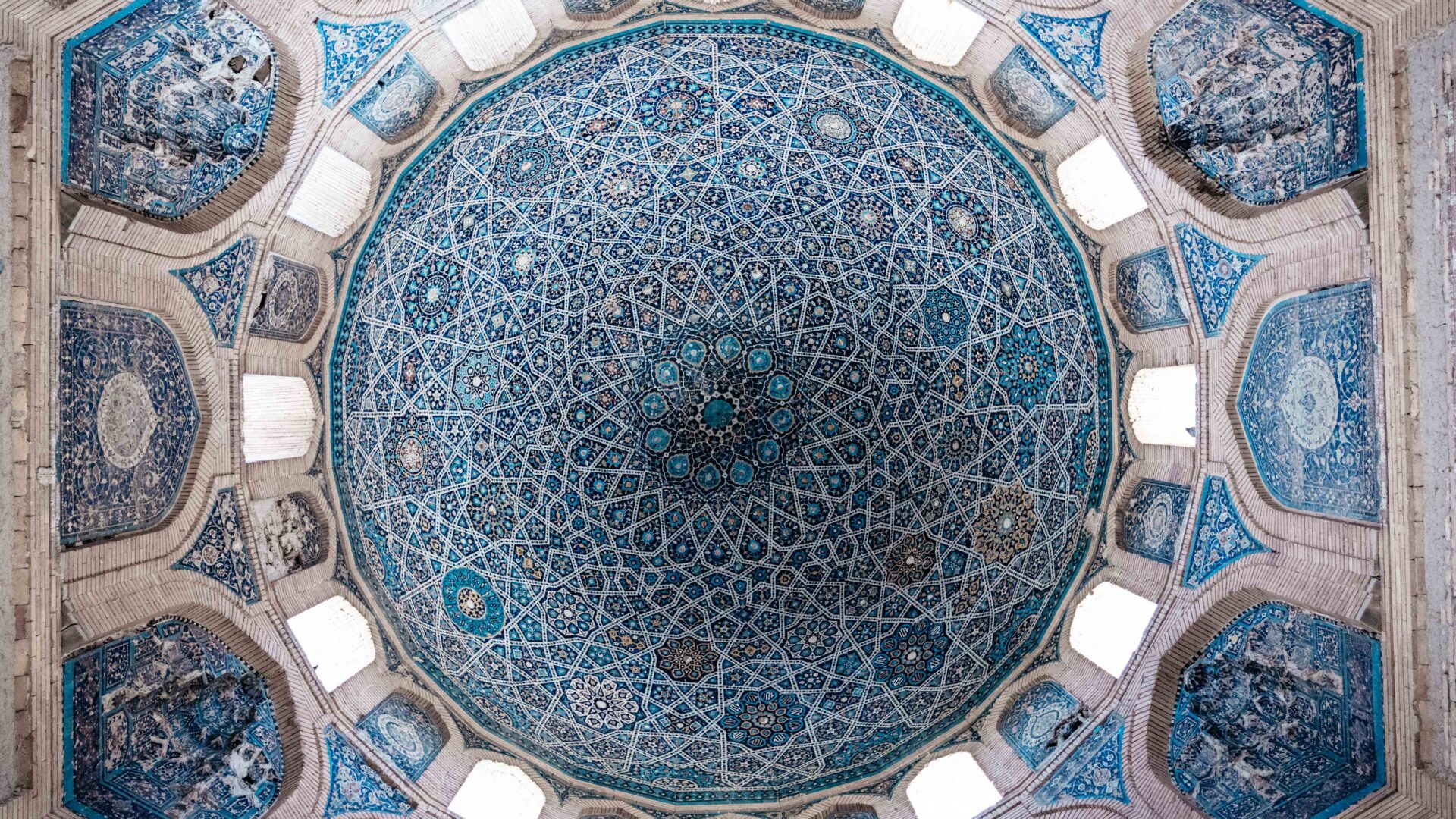

The Silk Road, as it would later be called, is neither an actual road nor a single route. It refers to the historic network of trade routes that stretched thousands of miles across Eurasia connecting China with Europe. Grain, livestock, leather, precious stones, porcelain, wool, gold and, of course, silk were transported along its network of trading posts and markets. As a consequence, two thousand years ago affluent Romans could garb themselves in silk clothes made in China while gold coins bearing Caesar’s image were spent in spice markets in India.

It was not only goods that travelled these routes but knowledge, religions and people too. Gunpowder, the magnetic compass, the printing press, and advanced mathematics all came to Europe from China and the Islamic world. Buddhism, Christianity and Islam each found new converts in the lands that opened up to the East and West. Along these same routes, Mongol armies swept across Eurasia — as did bubonic plague, travelling with merchants and their animals.

These exchanges had a profound impact on the empires and civilisations through which they passed, giving them political, religious and cultural shape. Many of the more networked cities developed into hubs of culture and learning and, in some, the sparks of a golden age were ignited.

By the late 16th century, the Silk Road had lost its prominence to new maritime trade routes but the legacy of interconnectivity and exchange endured. Today, it is being reimagined on an unprecedented scale. Through China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Eurasia is the focus of the largest and most expensive infrastructure project in history. If realised, a massive network of roads, railways, pipelines and ports could connect as much as 65% of the world’s population and radically alter the flow of global trade. It is already beginning to reshape Eurasia, focusing world attention once again on the exchange of goods and ideas running from East to West. While these investments will bring enormous opportunities, they come with many risks, especially for Central Asia. Regional insecurity, rising inequality, cultural dislocation, resource scarcity and climate change — all these must be mediated if the new Silk Road is to deliver prosperity to all of those who live along it.

The Aga Khan Foundation & The Silk Road

The Aga Khan Foundation and agencies of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) have been active in countries along the Silk Road for decades. AKDN is a long-term partner in the development of Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan.

Alongside its partners, AKDN has channelled significant financial and human resources into economic, social and cultural development in these regions. Promoting pluralism, self-reliance and women’s empowerment have been central to those efforts. AKDN’s initiatives are wide-ranging and include agriculture and food security, climate resilience, education, energy, enterprise development, financial services, healthcare, infrastructure, telecommunications and promoting civil society. It has also restored hundreds of historical monuments, parks and gardens and supported some of Central Asia’s greatest musicians to transmit their knowledge and perform on the world’s stage. AKDN’s overarching aim is to improve the quality of life.

This exhibition

The Silk Road: A Living History invites you to take a journey from London to Beijing, encountering some of the people, places and cultures in-between. The exhibition aims to celebrate the diversity found along this route, explore how historical customs live on today, and reveal connections between what appear at first glance to be very different cultures. Ultimately, the exhibition aims to help build bridges of interest and understanding between distant places and challenge perceptions of less well-known or understood parts of the world. The exhibition was created by Christopher Wilton-Steer, a travel photographer and Head of Communications at the Aga Khan Foundation (UK).

This exhibition is not an exhaustive photographic documentation of Eurasia’s people and cultures. It is a record of some of those Christopher encountered over the course of an overland journey from London to Beijing that he undertook in 2019 and therefore reflects only a fraction of the realities of these places. It is one of an infinite number of stories that could be told.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank first and foremost the wonderful and kind people I met on my travels and who allowed me into their lives. I am grateful to Simon Norfolk, Gary Otte, Andrew Quilty, Sebastian Schutyser and Kapila Productions for allowing me to use some of their photographs of places or events I was unable to visit on my journey. I would like to acknowledge the invaluable travel advice I received from Wild Frontiers and Eastern Turkey Tours, and the support from King’s Cross Central General Partner Ltd. who have allowed for this exhibition to take place in this public space. Lastly, I would like to thank my colleagues across the Aga Khan Development Network for their support and especially the Aga Khan Foundation who shared in the vision for this exhibition.

Christopher Wilton-Steer