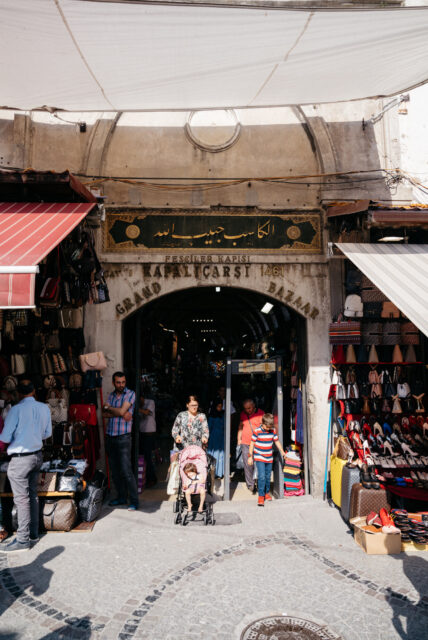

Considered one of the first shopping malls of the world, construction of the Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar began soon after the conquest of the city by the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Over the next 150 years it expanded in size but by the beginning of the 17th century it had taken on the form we know today.

Comprising 61 covered streets and over 4,000 shops, this enormous trade hub employs some 26,000 people. It attracts between 250,000 and 400,000 visitors daily. A staggering 90m people pass through it each year.

During the height of the Ottoman Empire the Bazaar was the hub of the Mediterranean trade and an engine of trade along the Silk Road. European travellers marvelled at the abundance and variety of goods that were bought and sold here.

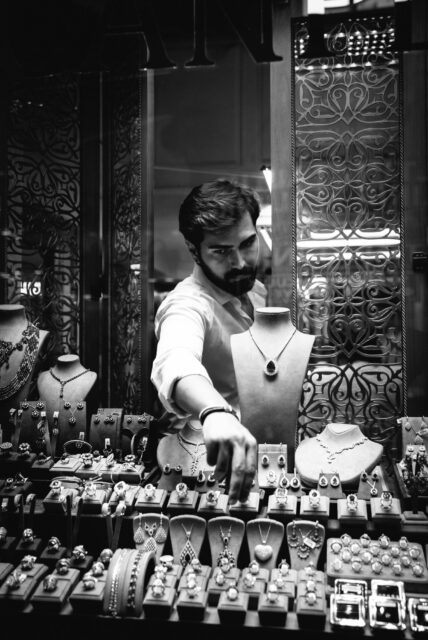

Today, its vaulted passageways are still lined with shops selling everything from cheap plastic products to luxury Persian carpets.

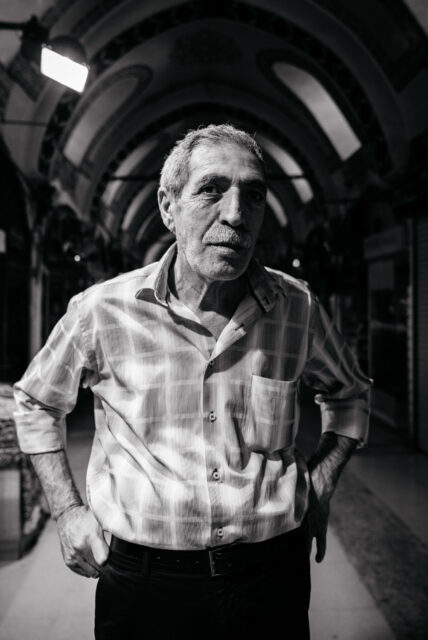

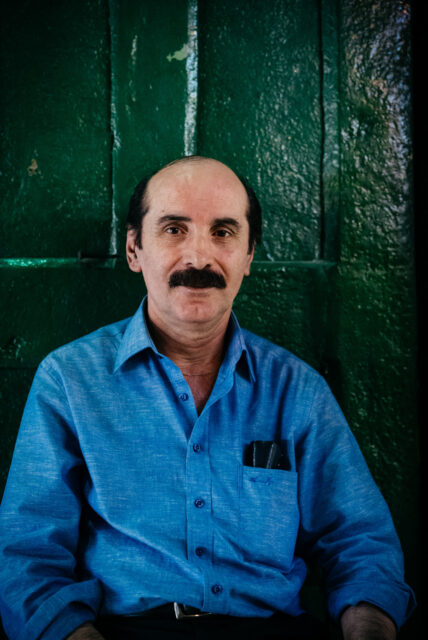

It’s easy to get lost and lose track of time in this vast labyrinth. After completely losing my bearings, I took refuge at a cafe that had been in Bekir Tezçakar’s family for four generations. Bekir insisted I try the home-made lemonade. I obliged and happily quenched my thirst whilst chatting to an Iraqi trader with bright blue eyes.

After a brief pit stop I set off in the direction of one of the exists he helpfully pointed in the general direction of. Some time later, I eventually found my way out.