Images of the spectacular ceilings that can be found in Uzbekistan and of the palaces, mosques, madrasahs and mausolea they belong to.

These photos were taken on my overland journey from London to Beijing in 2019.

Click on the right-hand side to travel east, click on the left-hand side to travel west.

Access captions and additional content by clicking MORE at the bottom.

See where you are on the journey by clicking MORE at the bottom and then MAP.

Learn about the exhibition at any time by clicking ABOUT in the top right.

Click on the country names along the top to skip to those countries.

This exhibition is better suited to desktop than mobile.

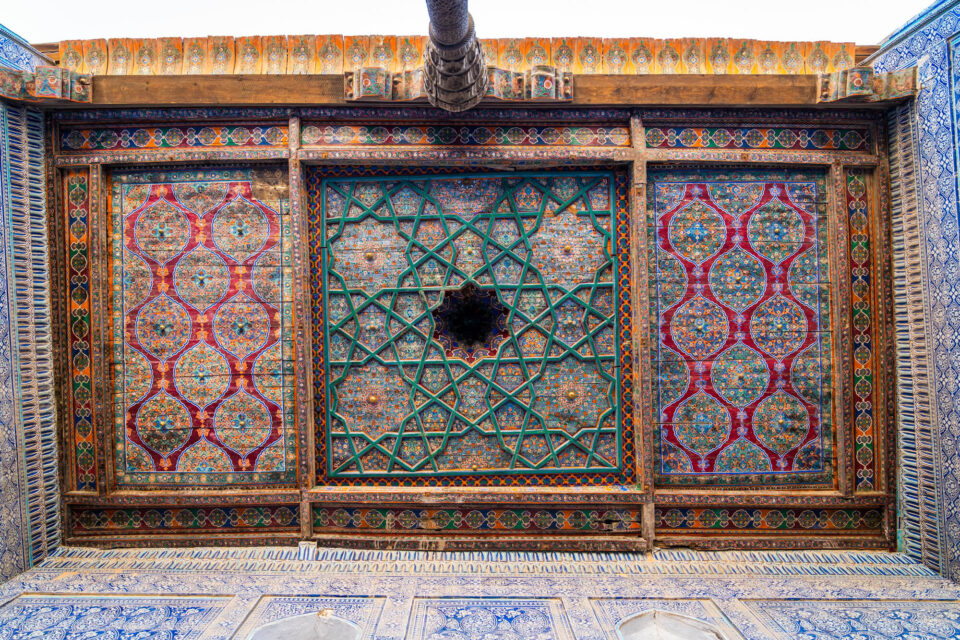

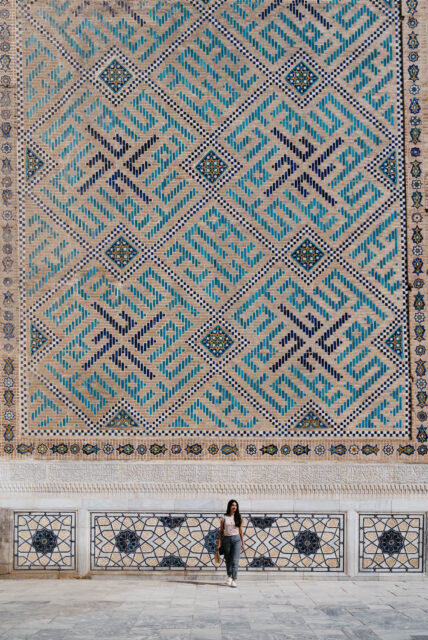

The historic centre of Khiva is well preserved and is very much the Silk Road desert city of the imagination. Located along a key axis of the Silk Road, Khiva became hugely prosperous from the trade that flowed through it, especially of people. It was once one of the largest slave markets of Central Asia.

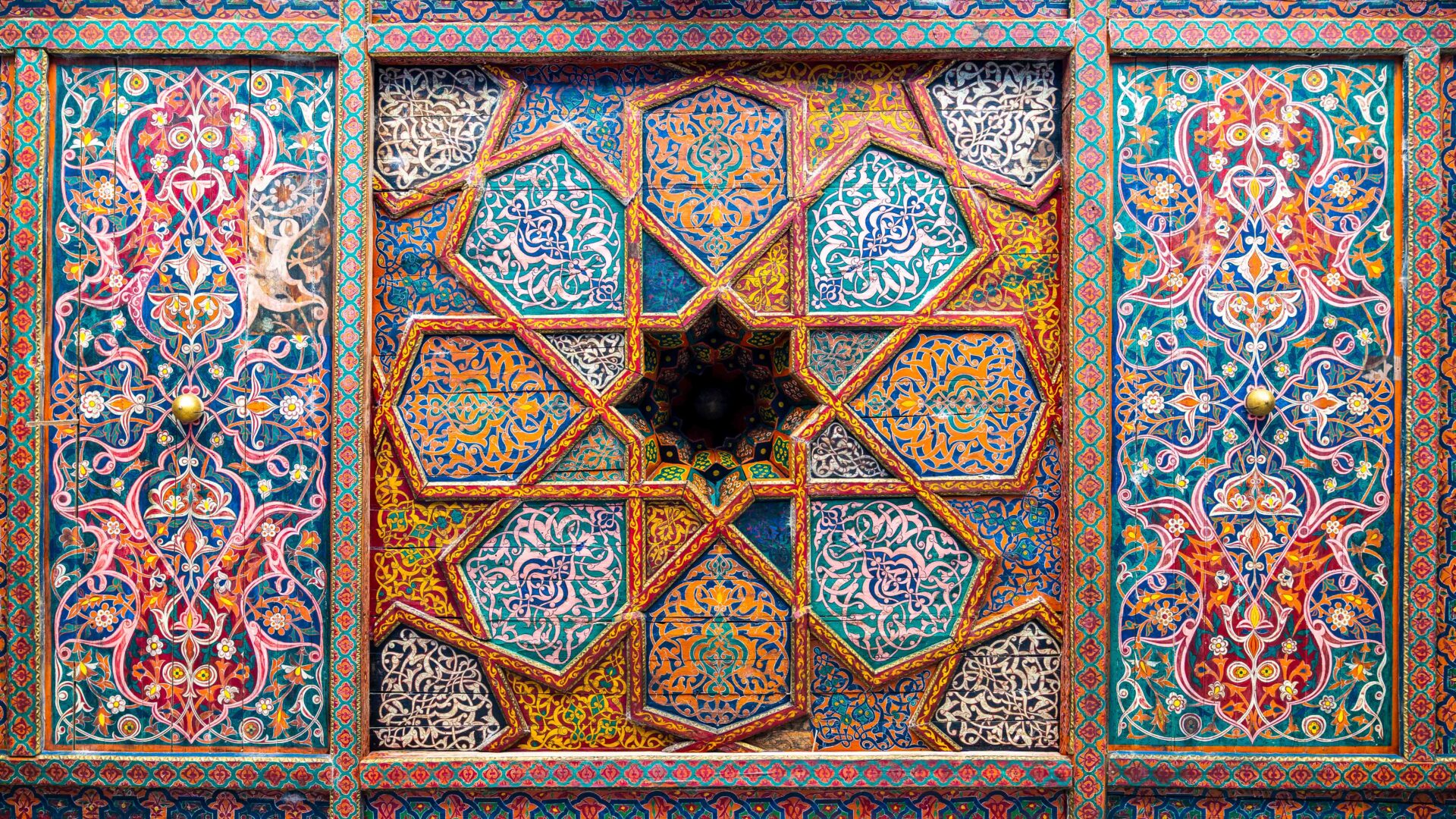

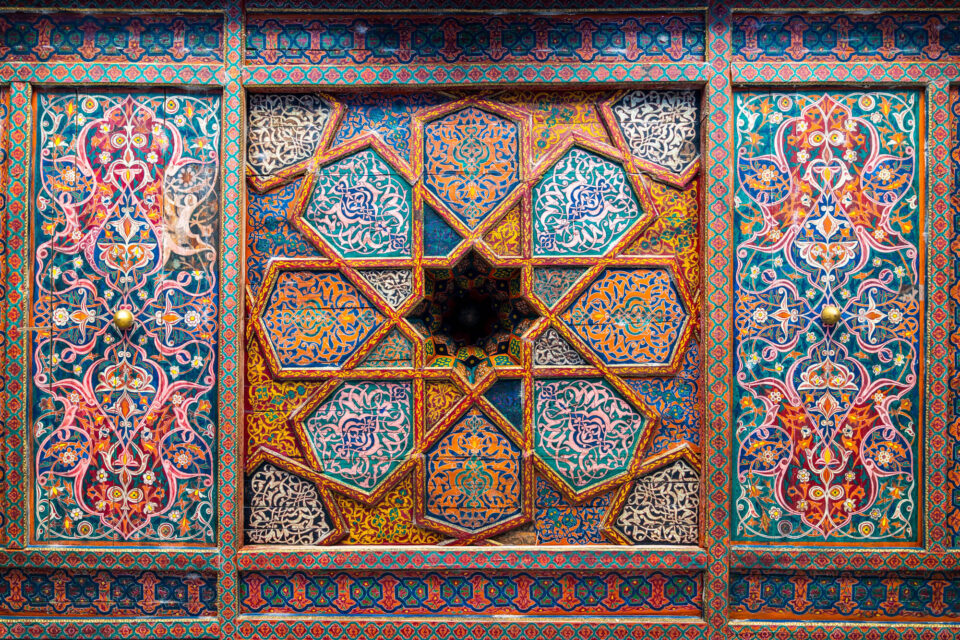

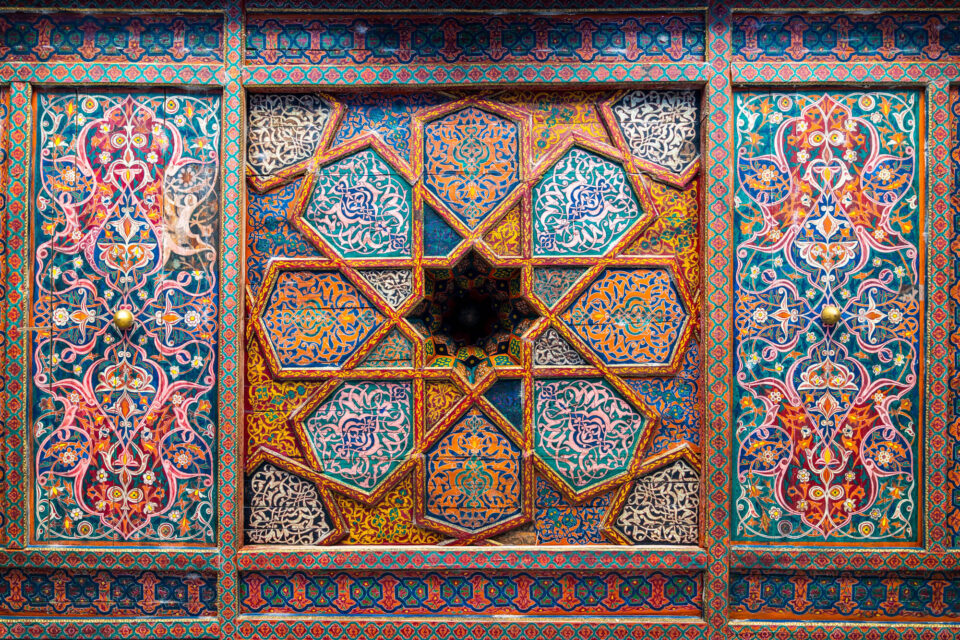

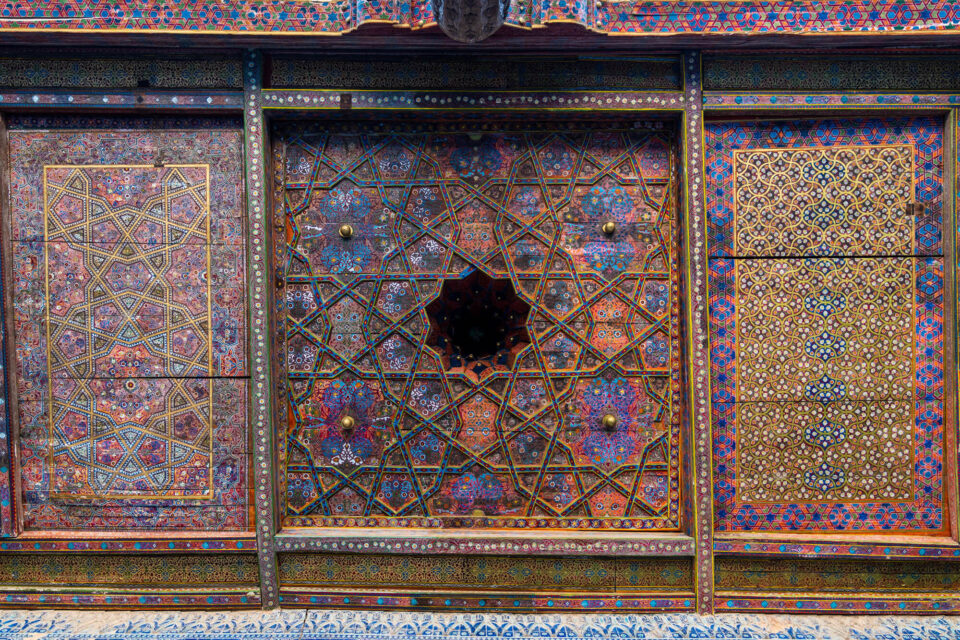

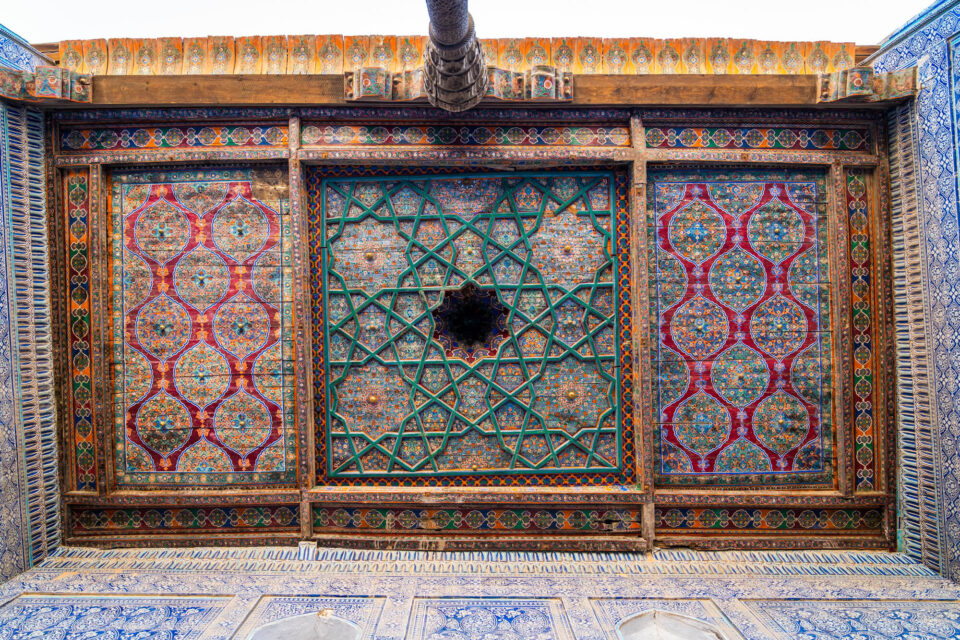

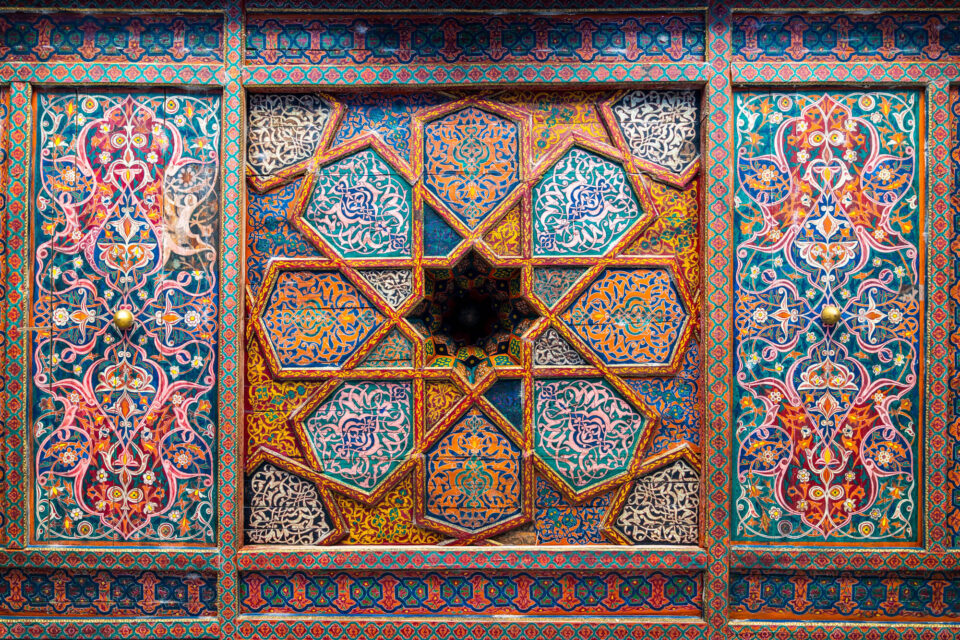

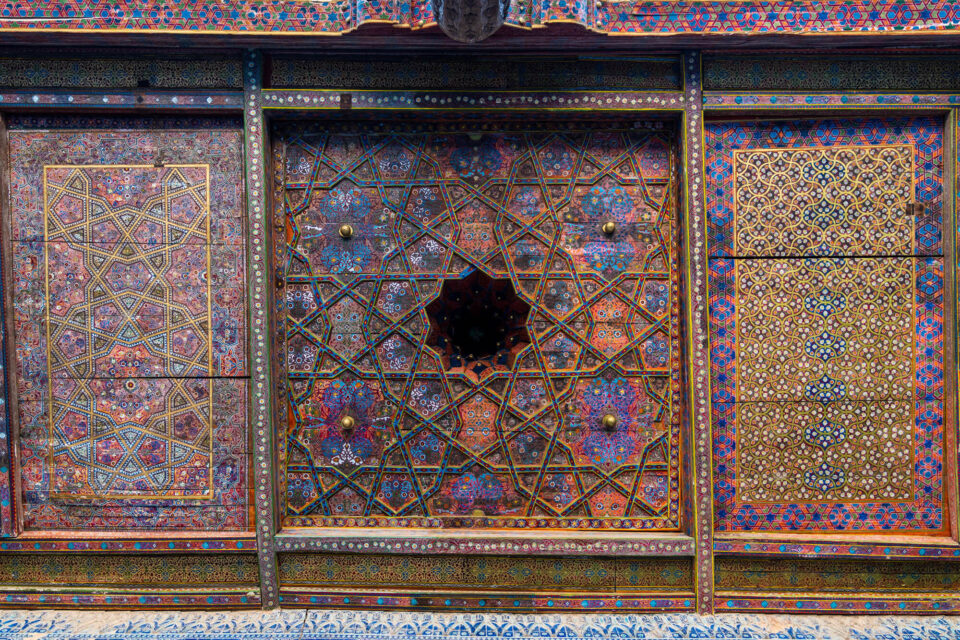

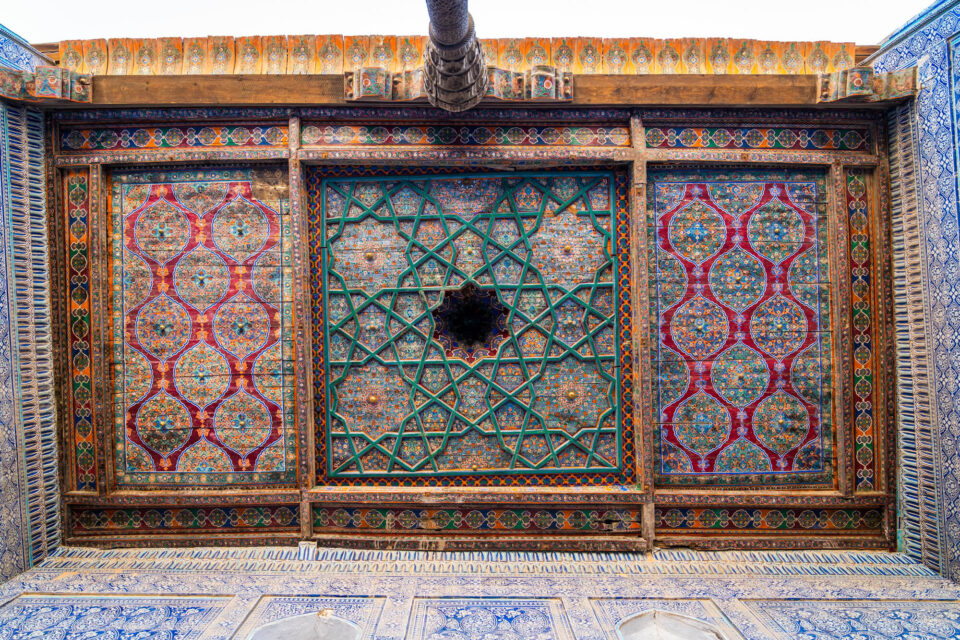

One of the ceilings of Khiva’s Tash Hauli Palace which brings together Islamic geometric designs decorative floral patterns, and colours typical of Central Asia.

Images of the spectacular ceilings that can be found in Uzbekistan and of the palaces, mosques, madrasahs and mausolea they belong to.

These photos were taken on my overland journey from London to Beijing in 2019.

Craftsmanship is still very much alive in Khiva and has an important role to play in the preservation of the old city.

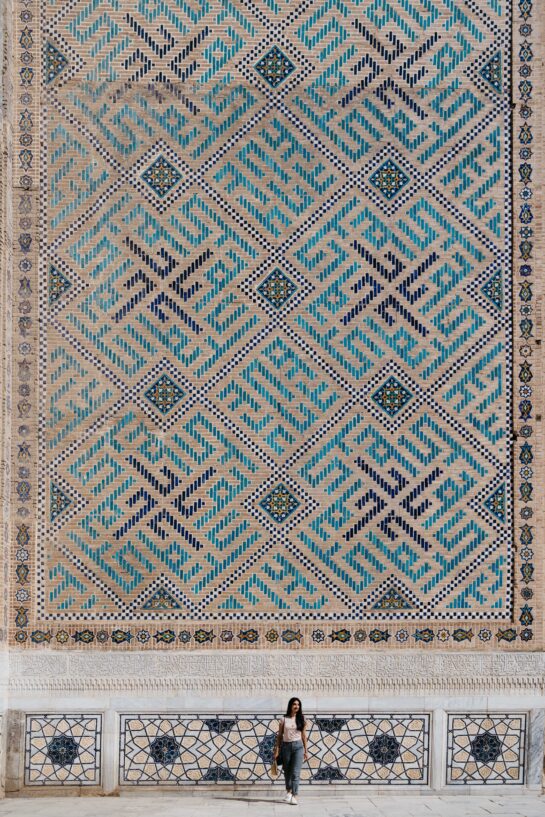

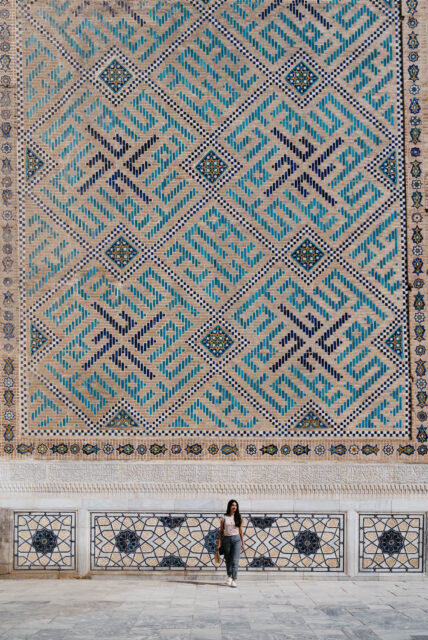

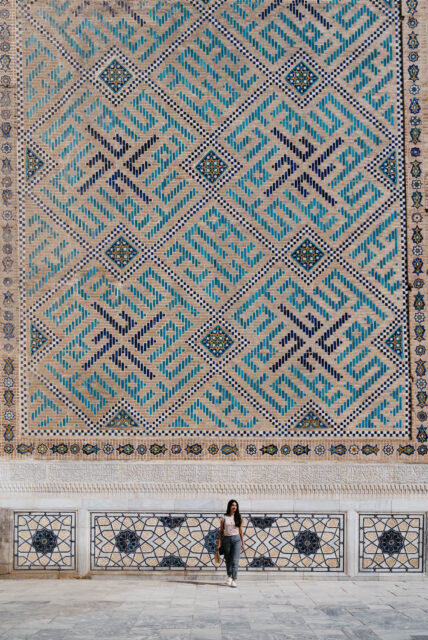

Khiva’s iconic blue tiles that cover the surfaces of the city’s palaces were introduced by invading Persian armies in the 18th century. They were much admired by the ruling Khan so the production of these tiles continued long after the raiders had been repelled.

A fashion show in the Nadir Divan-begi Madrasah not far from Bukhara’s old Jewish Quarter. The silk coats that the models wear fuse traditional Central Asian patterns with contemporary cuts to create something both old and new. The patterns are created using a technique called ikat whereby unwoven threads are tied off and dipped into dye. It is unknown when exactly this style came to Uzbekistan but by the 17th century ikat robes were worn by various royal families. Today, all members of society can be seen wearing these iconic patterns.

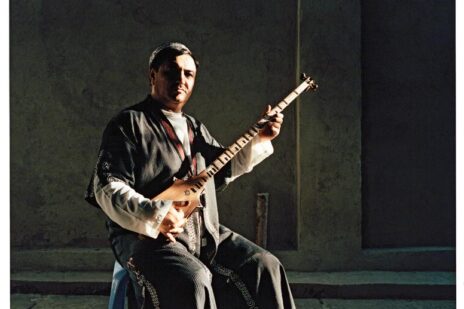

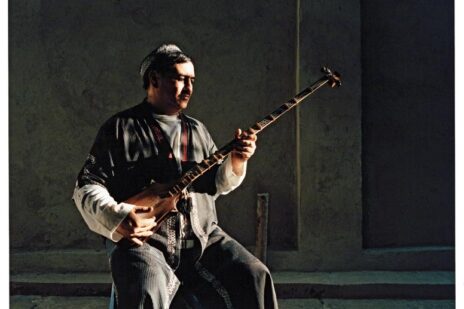

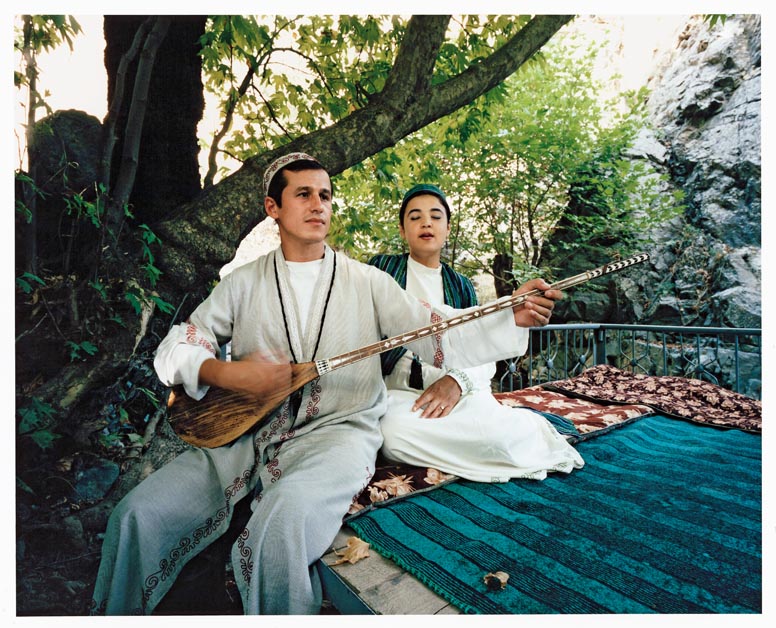

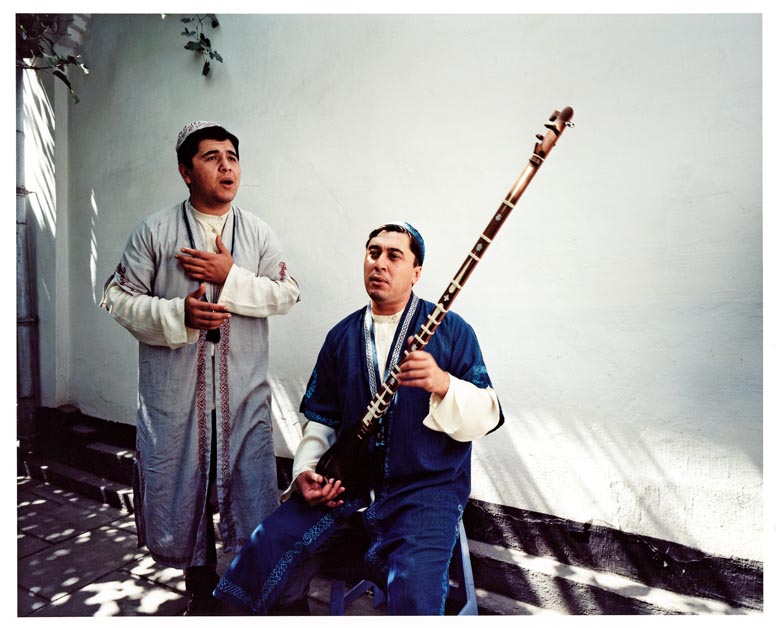

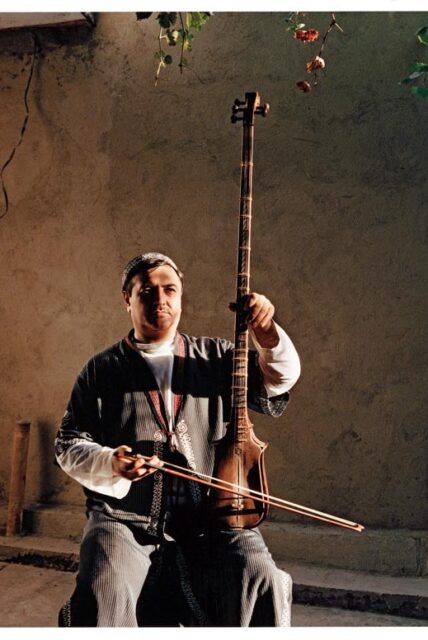

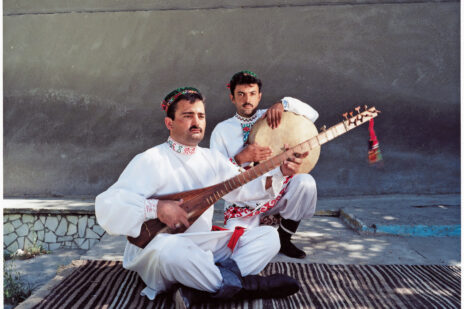

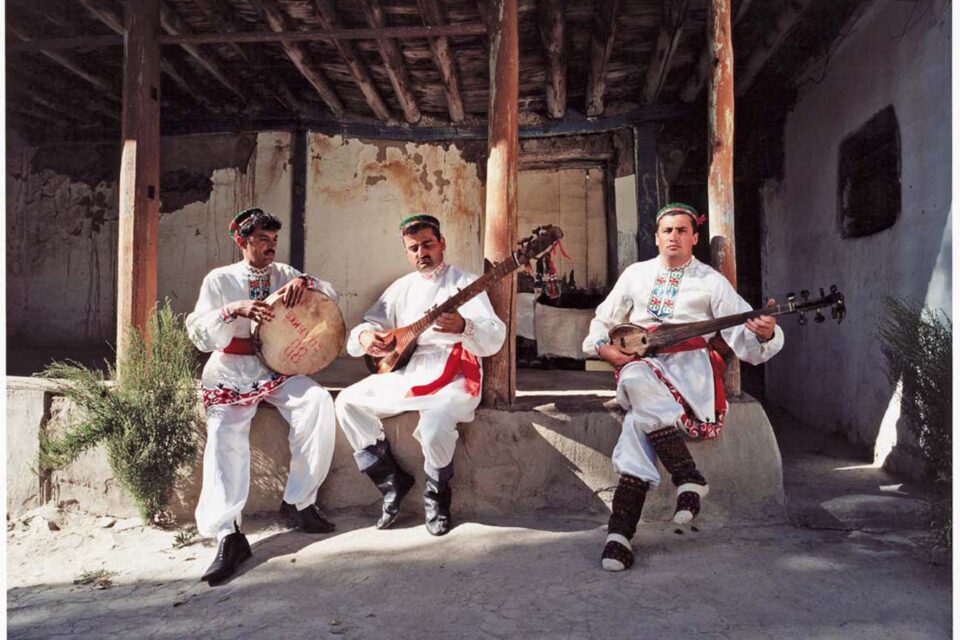

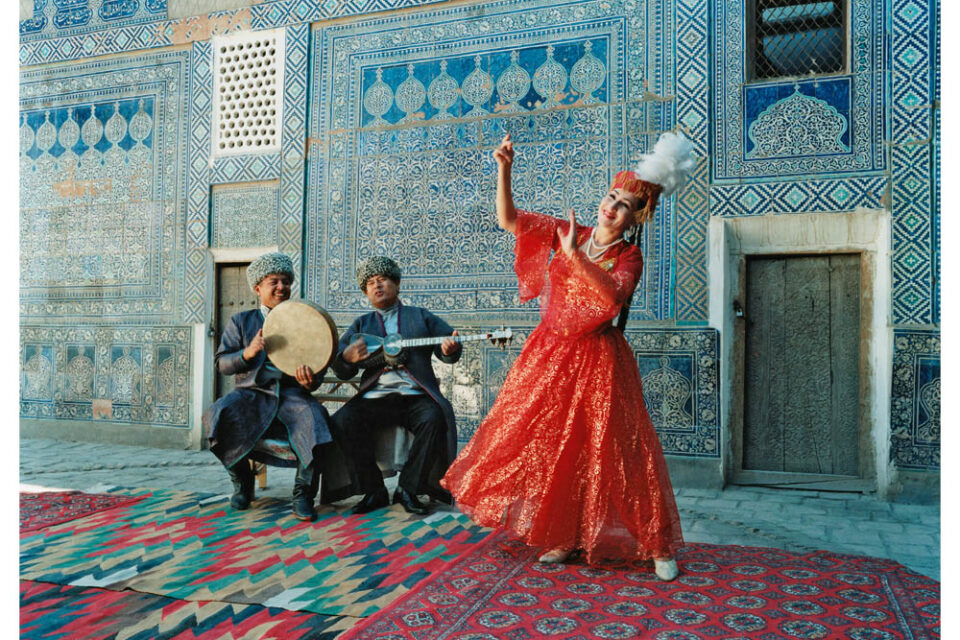

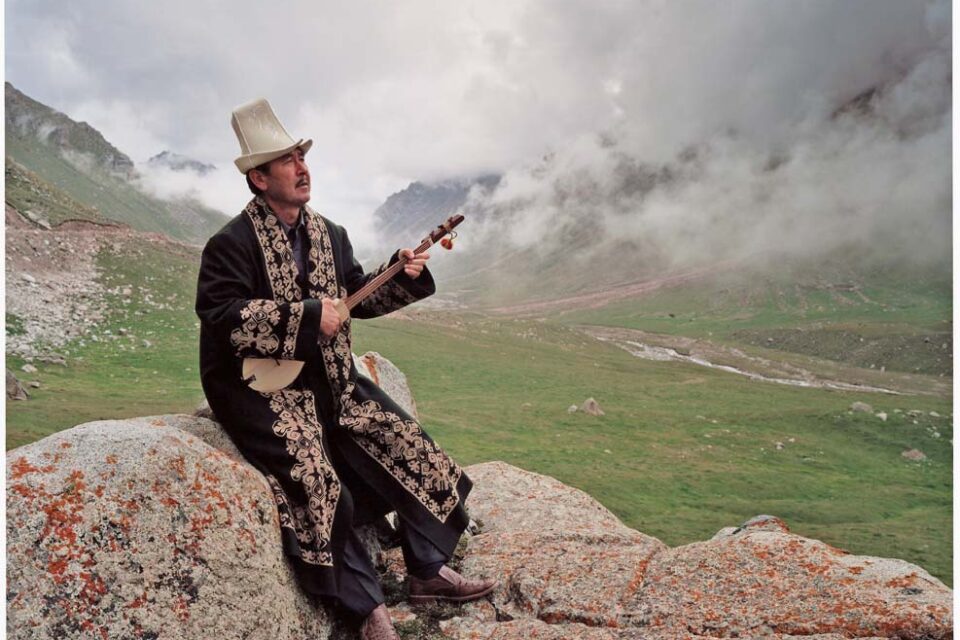

A young woman dances in the courtyard of the Sher-Dor madrasa. In recent decades, traditional forms of dance and music like these have become marginalised in the face of a globalised entertainment industry. To help nurture and promote traditional music in Central Asia, the Aga Khan Music Programme was established in 2000. The Programme helps document musical heritage, transmit knowledge to future generations and disseminate this work internationally through artistic collaborations. Thanks to Sebastian Schutyser for use of this photograph.

The mission of the Aga Khan Music Programme (AKMP) is to foster the development of living musical heritage in societies across the world where Muslims have a significant presence, and disseminate this work internationally through collaborations with exceptionally creative musicians, artists, educators, and arts presenters.

A key part of AKMP’s work to promote musical heritage are the triennial Aga Khan Music Awards. Established by His Highness the Aga Khan in 2018, recognise exceptional creativity, promise, and enterprise in music performance, creation, education, preservation and revitalisation in societies across the world in which Muslims have a significant presence. The inaugural Music Awards ceremony took place in Lisbon, Portugal from 29-31 March 2019, co-hosted by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the Lisbon Municipality.

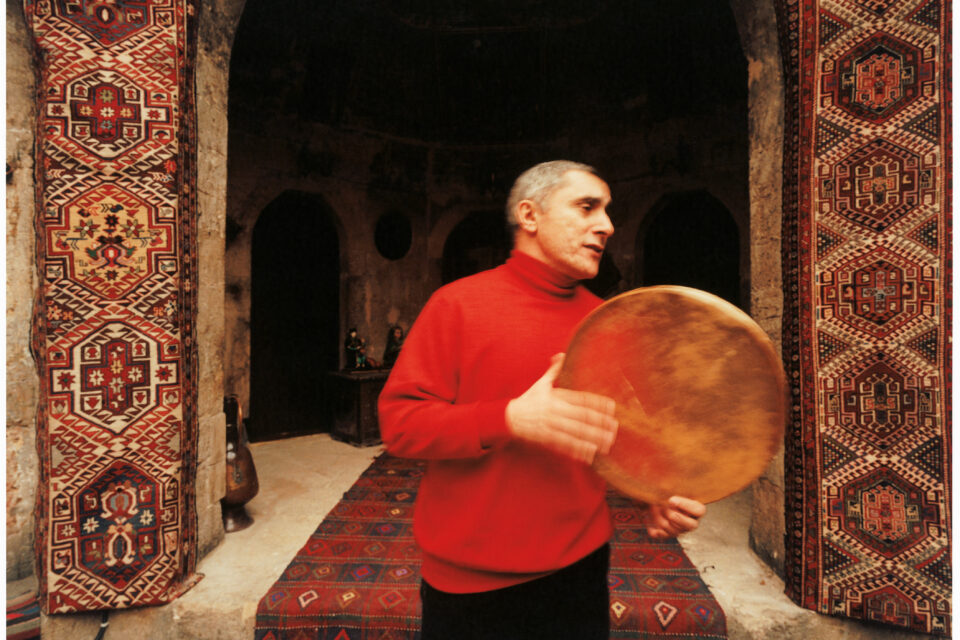

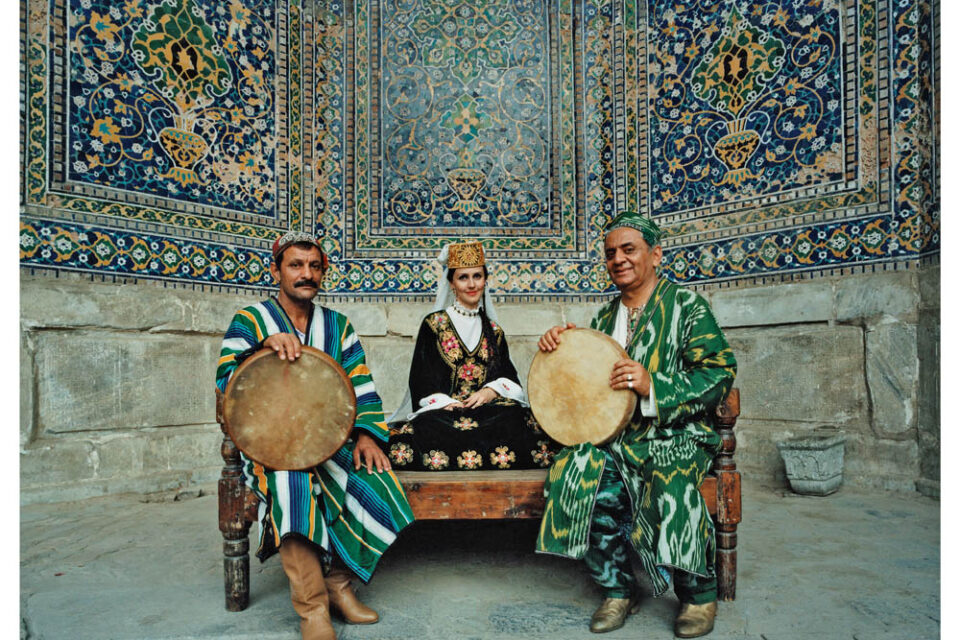

Enjoy the below photographs by Sebastian Schutyser.

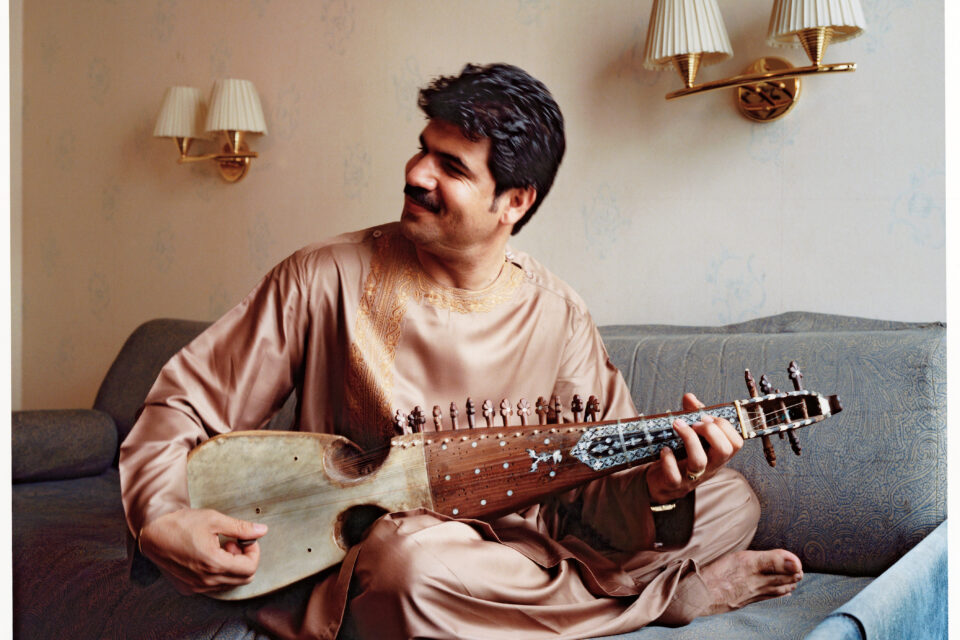

The Aga Khan Master Musicians create music inspired by their own deep roots in the cultures of the Middle East and Mediterranean Basin, South Asia, Central Asia, and China. Brought together by the Aga Khan Music Programme to explore how musical innovation can contribute to the revitalisation of cultural heritage, the Master Musicians are venerated performers and composer-arrangers who appear on the world’s most prestigious stages while also serving as preeminent teachers, mentors, and curators.

Visit this link for full concert: https://vimeo.com/showcase/8189844

Samarkand was the capital of the Timurid Empire and its many monuments are lavishly decorated. Several are crowned by turquoise domes and adorned by geometric tile work that spells out the names of God, the Prophet and Ali in Kufic calligraphy.

Images of the spectacular ceilings that can be found in Uzbekistan and of the palaces, mosques, madrasahs and mausolea they belong to.

These photos were taken on my overland journey from London to Beijing in 2019.

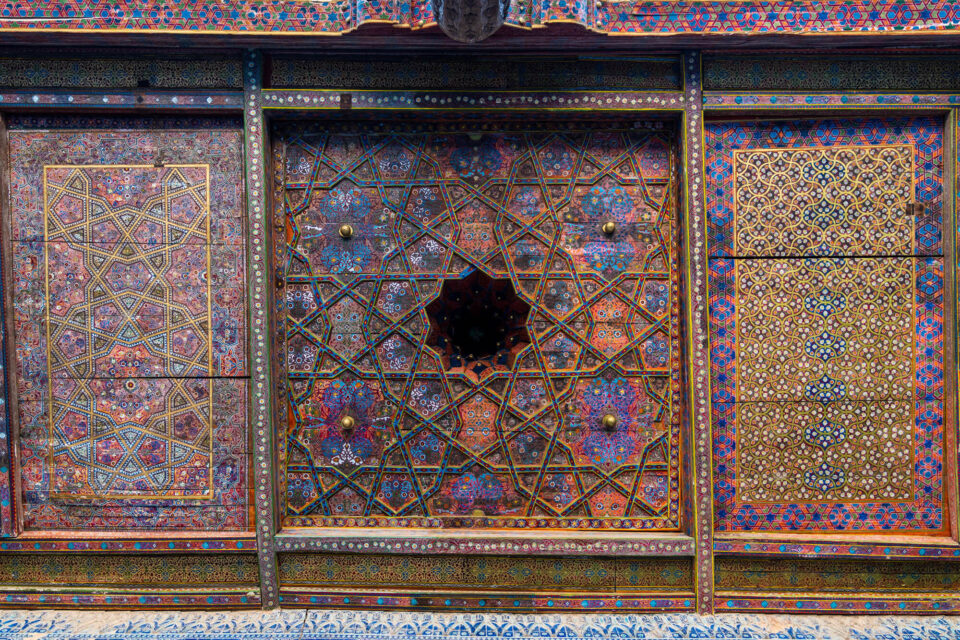

Images of the spectacular ceilings that can be found in Uzbekistan and of the palaces, mosques, madrasahs and mausolea they belong to.

These photos were taken on my overland journey from London to Beijing in 2019.

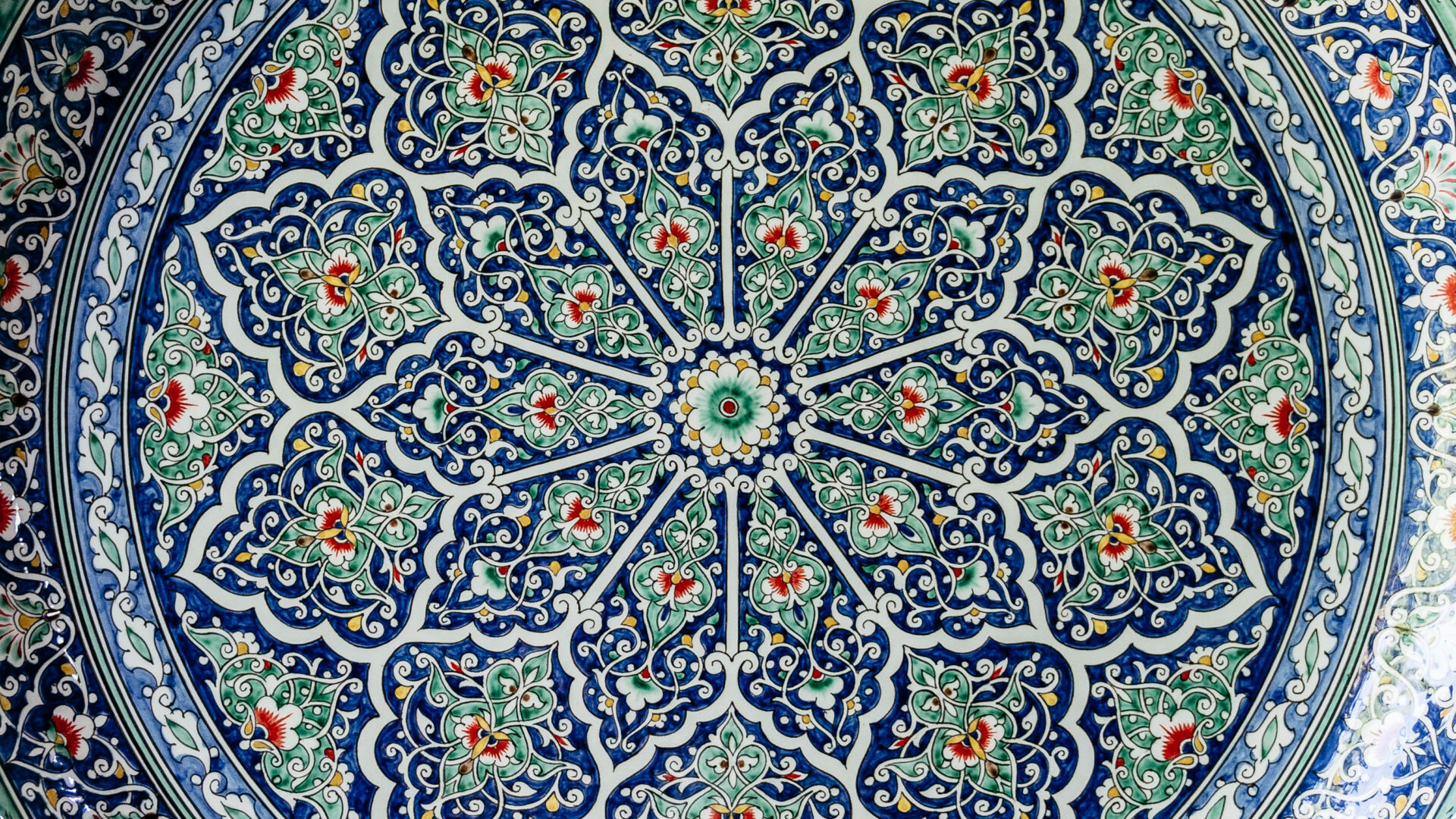

Uzbekistan is well known for its craft heritage. In eastern Uzbekistan, in and around the Fergana Valley, there is an abundance of artisanal workshops. Fergana is particularly well known for the production of ceramics which dates back to the 7th century. The workshop of Rustam Usmanov, one of Uzbekistan’s most celebrated, produces ceramics that combine Islamic geometric motifs with those found in nature like flowers and trees.

A winner of the UNESCO Award of Excellence, Rustam’s work is displayed in the State Hermitage in St Petersburg and is much sought after worldwide. One of Rustam’s young relatives creates a plate from clay and another carefully applies the glaze.

A man flattens paper at one of the oldest handmade paper-making workshops in Uzbekistan (left). A woman working silk on a loom at the Yodgorlik Silk Factory (middle). Silk has been produced in this region since the beginning of the 1st millennium CE (right).

In 138 BCE, General Zhang Qian of China’s Han Dynasty was sent on a diplomatic mission to develop economic and cultural links with the peoples of Central Asia. In so doing, he set in motion the creation of a transcontinental trade route that would shape the world as we know it today.

The Silk Road, as it would later be called, is neither an actual road nor a single route. It refers to the historic network of trade routes that stretched thousands of miles across Eurasia connecting China with Europe. Grain, livestock, leather, precious stones, porcelain, wool, gold and, of course, silk were transported along its network of trading posts and markets. As a consequence, two thousand years ago affluent Romans could garb themselves in silk clothes made in China while gold coins bearing Caesar’s image were spent in spice markets in India.

It was not only goods that travelled these routes but knowledge, religions and people too. Gunpowder, the magnetic compass, the printing press, and advanced mathematics all came to Europe from China and the Islamic world. Buddhism, Christianity and Islam each found new converts in the lands that opened up to the East and West. Along these same routes, Mongol armies swept across Eurasia — as did bubonic plague, travelling with merchants and their animals.

These exchanges had a profound impact on the empires and civilisations through which they passed, giving them political, religious and cultural shape. Many of the more networked cities developed into hubs of culture and learning and, in some, the sparks of a golden age were ignited.

By the late 16th century, the Silk Road had lost its prominence to new maritime trade routes but the legacy of interconnectivity and exchange endured. Today, it is being reimagined on an unprecedented scale. Through China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Eurasia is the focus of the largest and most expensive infrastructure project in history. If realised, a massive network of roads, railways, pipelines and ports could connect as much as 65% of the world’s population and radically alter the flow of global trade. It is already beginning to reshape Eurasia, focusing world attention once again on the exchange of goods and ideas running from East to West. While these investments will bring enormous opportunities, they come with many risks, especially for Central Asia. Regional insecurity, rising inequality, cultural dislocation, resource scarcity and climate change — all these must be mediated if the new Silk Road is to deliver prosperity to all of those who live along it.

The Aga Khan Foundation and agencies of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) have been active in countries along the Silk Road for decades. AKDN is a long-term partner in the development of Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan.

Alongside its partners, AKDN has channelled significant financial and human resources into economic, social and cultural development in these regions. Promoting pluralism, self-reliance and women’s empowerment have been central to those efforts. AKDN’s initiatives are wide-ranging and include agriculture and food security, climate resilience, education, energy, enterprise development, financial services, healthcare, infrastructure, telecommunications and promoting civil society. It has also restored hundreds of historical monuments, parks and gardens and supported some of Central Asia’s greatest musicians to transmit their knowledge and perform on the world’s stage. AKDN’s overarching aim is to improve the quality of life.

The Silk Road: A Living History invites you to take a journey from London to Beijing, encountering some of the people, places and cultures in-between. The exhibition aims to celebrate the diversity found along this route, explore how historical customs live on today, and reveal connections between what appear at first glance to be very different cultures. Ultimately, the exhibition aims to help build bridges of interest and understanding between distant places and challenge perceptions of less well-known or understood parts of the world. The exhibition was created by Christopher Wilton-Steer, a travel photographer and Head of Communications at the Aga Khan Foundation (UK).

This exhibition is not an exhaustive photographic documentation of Eurasia’s people and cultures. It is a record of some of those Christopher encountered over the course of an overland journey from London to Beijing that he undertook in 2019 and therefore reflects only a fraction of the realities of these places. It is one of an infinite number of stories that could be told.

I would like to thank first and foremost the wonderful and kind people I met on my travels and who allowed me into their lives. I am grateful to Simon Norfolk, Gary Otte, Andrew Quilty, Sebastian Schutyser and Kapila Productions for allowing me to use some of their photographs of places or events I was unable to visit on my journey. I would like to acknowledge the invaluable travel advice I received from Wild Frontiers and Eastern Turkey Tours, and the support from King’s Cross Central General Partner Ltd. who have allowed for this exhibition to take place in this public space. Lastly, I would like to thank my colleagues across the Aga Khan Development Network for their support and especially the Aga Khan Foundation who shared in the vision for this exhibition.

Christopher Wilton-Steer